Substack latest.

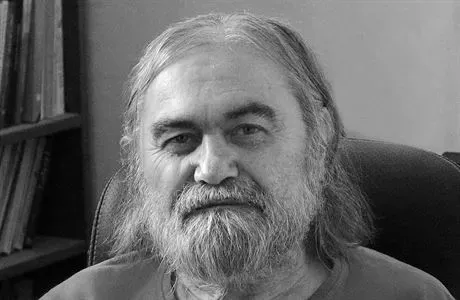

That philosophers disagree is a fact about which there is little disagreement, even among philosophers. But what this widespread and deep disagreement signifies is a topic of major disagreement. One issue is whether or not the fact of disagreement supplies a good reason to doubt the possibility of philosophical knowledge. Czech philosopher Jiří Fuchs says it doesn’t. I say it does.

Thanks, Bill. As we’ve discussed a few times, I agree with you that knowledge entails objective certainty. This is a defensible position, though many epistemologists reject it, often because it’s thought to entail epistemic skepticism.

One challenge is to articulate what objective certainty is.

Do you have a position on what constitutes objective certainty?

Consider some options:

A. S is objectively certain that p iff S’s justification for p entails that p, and S’s justification is itself infallible.

B. S is objectively certain that p iff S’s justification for p entails that p, S’s justification is itself infallible, and S is aware of both the entailment and the infallibility of the justification.

C. S is objectively certain that p iff S’s justification for p is indefeasible.

D. S is objectively certain that p iff S’s justification for p is indefeasible, and S is aware of the indefeasibility of his justification.

E. S is objectively certain that p iff, given S’s justification for p, S cannot be wrong that p.

F. S is objectively certain that p iff, given S’s justification for p, S cannot be wrong that p, and S is aware that he cannot be wrong that p given his justification.

One way to proceed would be by giving examples of objective certainty and examples of objective uncertainty and then isolating what makes them different. So what am I objectively certain of? That I seem to see a coyote, a rattlesnake, a man on a bike, etc. Here is an infinity of examples. Felt pain, pleasure, etc. Felt calm is a subjective state, but I am objectively certain that I am in it, or at least that calm is experienced here and now. That objects of all sorts appear is obj. certain. What is not objectively certain is that a given intentional object really exists. Any proposition the negation of which is a contradiction is a candidate for objectively certain status. LNC is a candidate. But not the existence of God.

Could we say that S is objectively certain that p iff it is impossible that S be mistaken about p? Could we say that objective certainty is just impossibility of mistake?

I agree with your method of distinguishing between the obj. certain and the obj. uncertain. I also agree with your examples of the obj. certain: seeming to see objects, the LNC, etc. And I accept the examples of the obj. uncertain: that the given intentional object really exists, etc.

“Could we say that S is objectively certain that p iff it is impossible that S be mistaken about p? Could we say that objective certainty is just impossibility of mistake?”

Yes, I think that’s a defensible characterization of obj. certainty.

The position that knowledge entails obj. certainty is unpopular with some philosophers because they take it to entail a widespread (though not global) skepticism, and they reject such skepticism. If knowledge entails obj. certainty, then much of what people take themselves to know about ordinary matters they don’t really know. (E.g., that there really is a coyote crossing the road, that there is a tree in the yard, that GW was the first POTUS, that Georgia is north of Florida, that the Dodgers won the 2025 World Series, etc.)

Back to Fuchs: “Fuchs insists that we have no good reason to be skeptical about the possibility of philosophical knowledge.”

If there is a good reason to hold that knowledge entails objective certainty, then there is a good reason to be skeptical about the possibility of philosophical knowledge, since the typical claims of philosophy are not ones for which it’s impossible that we are mistaken.

(By the way, if there’s a good reason to hold that knowledge entails objective certainty, then there’s a good reason to be skeptical about knowledge-claims in the hard sciences as well.)

Elliot,

Two quick points that I believe we both accept. Doubt is not denial. To doubt a proposition is not to deny that it is true, any more than to entertain a proposition is to affirm it to be true.

The other point is that there are degrees of doubt. Whether or not there is an objective measure of dubiety, subjectively, doubts comes in degrees as does credibility. I find highly credible what Jonathan Turley says about the law, much more credible than what DJT says about it. Claims made by Kamala Harris are far more dubious than claims made by Tulsi Gabbard.

Bill, I accept both points. Doubt is not denial, and there are degrees of doubt.