On occasion we encounter morally good people who are sincerely interested in our spiritual welfare, so much so that they fear that we will be lost if we differ from the views they cherish, even if our views are not so very different from theirs. Julian Green in his Diary 1928-1957, entry of 10 April 1929, p. 6, said to André Gide:

On occasion we encounter morally good people who are sincerely interested in our spiritual welfare, so much so that they fear that we will be lost if we differ from the views they cherish, even if our views are not so very different from theirs. Julian Green in his Diary 1928-1957, entry of 10 April 1929, p. 6, said to André Gide:

With the best will in the world, they never see you without a lurking idea of proselytism. They are worried about our salvation. They visibly have it on their minds., even when you talk to them of quite different matters. . . . “Yes indeed!” cries Gide. “They will use every means to draw you to them. When you are with them you find yourself in the situation of a woman faced with a man who would harbor intentions!”

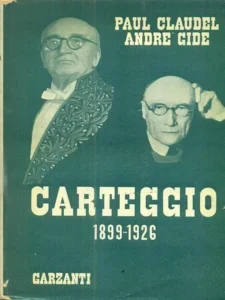

I’d guess the alacrity and enthusiasm of Gide’s response to Green had its origin in Gide’s relation to Paul Claudel, a committed Roman Catholic who never ceased trying to bring Gide around to the true faith. The Claudel-Gide correspondence 1899-1926 makes for fascinating reading.

What I find objectionable about the proselytic mentality is the cocksurety with which the proselytes hold their views. They dogmatically affirm this and they dogmatically deny that, and are not in the least troubled by the fact that people as intellectually and morally virtuous as they are disagree. They ‘know’ what salvation is and the way to it. The critical attitude is foreign to them. The fervor of their beliefs boils over into something they wrongly consider knowledge.

Their attitude is mostly harmless, but there are toxic forms of it, as history has taught us. The Founders of our great republic were well aware of the religious wars and of the blood shed by the dogmatists. These days it is the spikes of the Islamic trident that are a clear and present threat: conversion, dhimmitude, the sword. The ascension of a madman to the mayoralty in our greatest city is a troubling sign.

“What I find objectionable about the proselytic mentality is the cocksurety with which the proselytes hold their views. They dogmatically affirm this and they dogmatically deny that, and are not in the least troubled by the fact that people as intellectually and morally virtuous as they are disagree. They ‘know’ what salvation is and the way to it. The critical attitude is foreign to them. The fervor of their beliefs boils over into something they wrongly consider knowledge.”

Bill, I also find this mentality objectionable. As you noted, there are toxic forms evident in the historical record. Other objectionable forms concern not bloodshed but manipulation and unreasonableness. Here’s an example. I once heard a young pastor at a “nondenominational” Christian church say that Christian believers should befriend non-believers. He immediately gave a supporting reason: non-believers are opportunities for proselytism; befriending them is a means to convert them. He gave no other reason for forming such friendships. His tone seemed dogmatic.

I find this kind of attitude objectionable. As if the only reason to seek a friendship with someone of a different perspective is to convert that person to one’s own view! Of course, in a good friendship, natural opportunities for such conversations might arise. But what concerned me about the mindset was that it seemed (a) manipulative, (b) unreasonably confident about matters of morality and salvation, (c) inappropriately self-assured, and (d) unjustifiably ignorant of (a) – (c).

Thanks for the comment, Elliot. We will agree that there is nothing objectionable about trying to persuade people of this or that. For example, in recent posts I have been trying to persuade Thomists such as Ed Feser that hylomorphism in the philosophy of mind is inadequate when it comes to rendering intelligible personal survival post-mortem. But the tone of my posts makes it clear that I am open to refutation: I am by no means certain that I am right. It is just that so far no one has shown me to be wrong.

What offends both of us is the conceit of some that they possess the truth, when, as it seems to us, they have no right to their cocksurety. (By the way, that is a recognized English word and not my coinage.)

But far more offensive are those who say they will pray for you if you disagree with them, especially when their intent is malign, as when Nancy Pelosi said she would pray for Trump. She really fancies herself to be a good person and Trump evil when the truth is that she is worse than him intellectually and morally. Her support for abortion, for example.

Bill, I agree that there’s nothing objectionable about trying to persuade people of this or that. I think that attempts at persuasion are natural to the human experience and appropriately found in all three kinds of Aristotelian friendship. For guys like us, the sort of debate you are having about hylomorphism is one of life’s treasures.

You’re right that we are both offended by the conceit of some that they possess the truth, when, as it seems to us, they have no right to their cocksurety. I’m familiar with that word. Interestingly, Russell used ‘cocksure’ in The Triumph of Stupidity: “The fundamental cause of the trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.” Russell was addressing an attitude similar to the sort we are discussing, though the context of his article is different from that of our discussion.

https://russell-j.com/0583TS.HTM

Here are a few things that bother me about the cocksure:

– the conceit you noted;

– the motive that one should seek friendship only for the sake of persuading the friend to accepts one’s ‘certainty;’*

– the lack of intellectual virtues such as epistemic humility, fairmindedness, and respect for rational autonomy.

In a good persuasive debate, as you noted, the interlocutors believe that they are right but don’t take themselves to be objectively certain that they are right. They have epistemic humility. But the would-be persuader who takes himself to be certain lacks epistemic humility and might well be unwilling to debate.

By the way, it seems to me that a Christian should be committed to the life of virtue, both intellectual and moral. Thus, one who claims to be Christian yet is unconcerned with virtue (moral and intellectual) is a curious case indeed.

And yes: it is prudent to be wary of those who fancy themselves good when they are not. We should be similarly wary of those who take themselves to be good merely because they accept some doctrine – as if there’s nothing more to being a good person than belonging to a group of people who agree on doctrinal matters.

* As you are aware, Aristotle’s three kinds of friendship are ones of utility, of pleasure, and of virtue. The cocksure seems to want to add a fourth: friendship of asymmetrical persuasion such that the cocksure saves the confused from error, while the confused adds nothing to the cocksure and there are no other aspects of the friendship.

Thanks for the link to the Russell essay. I wasn’t aware of it. “The fundamental cause of the trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.” That reminded me of William Butler Yeats, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43290/the-second-coming. The last two lines of the first stanza echo Russell (or is Russell echoing Yeats?)

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Recent events bode ill for the future. I expect you are aware of the ‘Groyper’ phenomenon. I’ll post something on that shortly.

Thanks for your response, Bill. I’m familiar with the poem by Yeats. It’s a very good one. I think it was published before Russell’s article.

I am not aware of the ‘Groyper’ phenomenon. I just looked it up. I look forward to your post on the topic.

The issue of cocksurety and its relevance to religion and politics is very interesting to me.