David Brightly in a recent comment writes,

[Laird] Addis says,

The very notion of language as a representational system presupposes the notion of mind, but not vice versa.

I can agree with that, but why should it presuppose consciousness too?

In a comment under this piece you write,

Examples like this cause trouble for those divide-and-conquerers who want to prise intentionality apart from consciousness with its qualia, subjectivity, and what-it-is-like-ness, and work on the problems separately, the first problem being supposedly tractable while the second is called the (intractable) Hard Problem (David Chalmers). Both are hard as hell and they cannot be separated. See Colin McGinn, Galen Strawson, et al.

Could you say a bit more on this?

I’ll try. You grant that representation presupposes mind, but wonder why it should also presuppose consciousness. Why can’t there be a representational system that lacks consciousness? Why can’t there be an insentient, and thus unconscious, machine that represents objects and states of affairs external to itself? Fair question!

Here is an example to make the problem jump out at you. Suppose you have an advanced AI-driven robot, an artificial French maid, let us assume, which is never in any sentient state, that is, it never feels anything. You could say, but only analogically, that the robot is in various ‘sensory’ states, states caused by the causal impacts of physical objects against its ‘sensory’ transducers whether optical, auditory, tactile, kinaesthetic . . . but these ‘sensory’ states would have no associated qualitative or phenomenological features. Remember Herbert Feigl? In Feiglian terms, there would be no ‘raw feels’ in the bot should her owner ‘feel her up.’ Surely you have heard of Thomas Nagel. In Nagelian terms, there would be nothing it is like for the bot to have her breasts fondled. If her owner fondles the breasts of his robotic French maid, she feels nothing even though she is programmed to respond appropriately to the causal impacts via her linguistic and other behavior. “What are you doing, sir? I may be a bot but I am not a sex bot! Hands off!” If the owner had to operate upon her, he would not need to put her under an anaesthetic. And this for the simple reason that she is nothing but an insensate machine.

I hope Brightly agrees with me that verbal and nonverbal behavior, whether by robots or by us, are not constitutive of genuine sentient states. I hope he rejects analytical (as opposed to methodological) behaviorism, according to which feeling pain, for example, is nothing more than exhibiting verbal or nonverbal pain-behavior. I hope he agrees with me that the bot I described is a zombie (as philosophers use this term) and that we are not zombies.

But even if he agrees with all that, there remains the question: Is the robot, although wholly insentient, the subject of mental states, where mental states are intentional (object-directed) states? If yes, then we can have mind without consciousness, intrinsic intentionality without subjectivity, content without consciousness.

Here are some materials for an argument contra.

P1 Representation is a species of intentionality. Representational states of a system (whether an organism, a machine, a spiritual substance, whatever) are intentional or object-directed states.

P2 Such states involve contents that mediate between the subject of the state and the thing toward which the state is directed. Contents are the cogitata in the following schema: Ego-cogito-cogitatum qua cogitatum-res. Note that ‘directed toward’ and ‘object-directed’ are being used here in such a way as to allow the possibility that there is nothing in reality, no res, to which these states are directed. Directedness is an intrinsic feature of intentional states, not a relational one. This means that the directedness of an object-directed state is what it is whether or not there is anything in the external world to which the state is directed. See Object-Directedness and Object-Dependence for more on this.

As for the contents, they present the thing to the subject of the state. We can think of contents as modes of presentation, as Darstellungsweisen in something close to Frege’s sense. Necessarily, no state without a content, and no content without a state. (Compare the strict correlation of noesis and noema in Husserl.) Suppose I undergo an experience which is the seeing as of a tree. I am the subject of the representational state of seeing and the thing to which the state is directed, if it exists, is a tree in nature. The ‘as of‘ locution signals that the thing intended in the state may or may not exist in reality.

P3 But the tree, even if it exists in the external world, is not given, i.e., does not appear to the subject, with all its aspects, properties, and relations, but only with some of them. John Searle speaks of the “aspectual shape” of intentional states. Whenever we perceive anything or think about anything, we always do so under some aspects and not others. These aspectual features are essential to the intentional state; they are part of what make intentional states the states that they are. (The Rediscovery of the Mind, MIT Press, 1992, pp. 156-157) The phrase I bolded implies that no intentional state that succeeds in targeting a thing (res) in external world is such that every aspect of the thing is before the mind of the person in the state.

P4 Intentional states are therefore not only necessarily of something; they are necessarily of something as something. And given the finitude of the human mind, I want to underscore the fact that even if every F is a G, one can be aware of x as F without being aware of x as G. Indeed, this is so even if necessarily (whether metaphysically or nomologically) every F is a G. Thus I can be aware of a moving object as a cat, without being aware of it as spatially extended, as an animal, as a mammal, as an animal that cools itself by panting as opposed to sweating, as my cat, as the same cat I saw an hour ago, etc.

BRIGHTLY’S THEORY (as I understand it, in my own words.)

B1. There is a distinction between subpersonal and personal contents. Subpersonal contents exist without the benefit of consciousness and play their mediating role in representational states in wholly insentient machines such as the AI-driven robotic maid.

B2. We attribute subpersonal contents to machines of sufficient complexity and these attributions are correct in that these machines really are intentional/representational systems.

B3. While it is true that the only intentional (object-directed) states of which we humans are aware are conscious intentional states, that they are conscious is a merely contingent fact about them. Thus, “the conditions necessary and sufficient for content are neutral on the question whether the bearer of the content happens to be a conscious state. Indeed the very same range of contents that are possessed by conscious creatures could be possessed by creatures without a trace of consciousness.” (Colin McGinn, The Problem of Consciousness, Blackwell 1991, p. 32.

MY THEORY

V1. There is no distinction between subpersonal and personal contents. All contents are contents of (belonging to) conscious states. Brentano taught that all consciousness is intentional, that every consciousness is a consciousness of something. I deny that, holding as I do that some conscious states are non-intentional. But I do subscribe to the Converse Brentano Thesis, namely, that all intentionality is conscious. In a slogan adapted from McGinn though not quite endorsed by him, There is no of-ness without what-it-is-like-ness. This implies that only conscious beings can be the subjects of original or intrinsic intentionality. And so the robotic maid is not the subject of intentional/representational states. The same goes for the cerebral processes transpiring in us humans when said processes are viewed as purely material: they are not about anything because there is nothing it is like to be them. Whether one is a meat head or a silicon head, no content without consciousness! Let that be our battle cry.

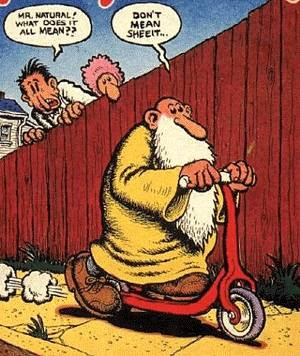

And so, when the robotic maid’s voice synthesizer ‘says’ ‘This shelf is so dusty!’ it is only AS IF ‘she’ is thereby referring to a state of affairs and its constituents, the shelf and the dust. ‘She’ is not saying anything, sensu stricto, but merely making sounds to which we original-Sinn-ers, attribute meaning and reference. Thinking reference (intentionality) enjoys primacy over linguistic reference. Cogitation trumps word-slinging. The latter is parasitic upon the former. Language without mind is just scribbles, pixels, chalk marks, indentations in stone, ones and zeros. As Mr. Natural might have said, “It don’t mean shit.” An sich, und sensu stricto.

V2. Our attribution of intentionality to insentient systems is merely AS IF. The robot in my example behaves as if it is really cognizant of states of affairs such as the dustiness of the book shelves and as if it really wants to please its boss while really fearing his sexual advances. But all the real intentionality is in us who makes the attributions. And please note that our attributing of intentionality to systems whether silicon-based or meat-based that cannot host it is itself real intentionality. It follows, pace Daniel Dennett, that intentionality cannot be ascriptive all the way down (or up). But Dennett’s ascriptivist theory of intentionality calls for a separate post.

V3. It is not merely a contingent fact about the intentional state that we our introspectively aware of that they are conscious states; it is essential to them.

NOW, have I refuted Brightly ? No! I have arranged a standoff. I have not refuted but merely neutralized his position by showing that it is not rationally coercive. I have done this by sketching a rationally acceptable alternative. We have made progress in that we now both better understand the problems we are discussing and our different approaches to them.

Can we break standoff? I doubt it, but we shall see.

Many thanks, Bill, and my apologies for a slow response. Let me assure you that I’m not a behaviourist and I agree that your android is a zombie. Your B1, B2, and B3 capture my position well. Your view I take to be that consciousness underlies intentionality underlies representation. My view is that representation underlies intentionality and both may be present in the absence of consciousness. I am interested in cases intermediate between the human and the machine. For example, a frog catching a fly with its tongue, a monkey reaching out to pluck a fruit, or a lion chasing down a zebra. I can’t rule out that there is some kind of consciousness in each of these cases, but it can’t be our kind of consciousness in which an unspoken but essentially linguistic commentary accompanies the passing scene all the waking hours. Regardless of the kind of consciousness present, I cannot imagine that these behaviours are possible without something that counts as an internal representation of the prey and that at the very least modulates the muscular movements required. And this seems to me a species of intentionality.

I followed up the link you gave in your recent piece on Gyula Klima’s Thomism. Husserl’s points all seem to make good sense with regard to images considered relative to vision as a given intentional system. But if we step back and ask how the intentionality arises it seems to me that we are faced with paradox. For vision itself begins with images (on the retinas) and ultimately delivers something at least akin to an image (enhanced with depth cues) in which we find ourselves seemingly immersed. After all that neural activity in the visual regions of the brain we arrive back almost to where we started with the retinal images. I want to say that the essence of intentionality is recognition. The frog’s brain has to decide if the distribution of firings in its optic nerves represents (corresponds to) an edible insect. Similarly for the monkey and lion. Likewise too the picture before me of a woman represents my mother (to me) if it produces a distribution of neural activity in my visual cortex that matches sufficiently well with a stored distribution derived from numerous encounters with a certain very significant person in my life. I am happy to call such distributions ‘images’ but they might be lists of Fourier coefficients, for all I know.

Let me apply this line of thought to just one argument you make in the Husserl piece:

The argument seems to be that image-like entities and resemblance cannot explain intentionality, contra my view above. And this because a photo of a ball-bearing cannot uniquely identify its causal source ball-bearing and hence can possesses no intrinsic intentionality. I agree. But my view does not require this. What it does require is that the image-like entities be parts of a larger whole that has the resources to make comparisons of resemblance between them. The comparison is between two internal entities, not one internal and one external.