1. Many philosophers of mind who eschew substance dualism opt for a property dualism. Allowing only one category of substances, material substances, they allow at least two categories of properties, mental and physical. An example of a mental property is sensing red, or to put it adverbially, the property of sensing redly, or in a Chisholmian variant, being-appeared-to-redly. Any sensory quale would serve as an example of a mental property. Their irreducibility to physical properties is the reason for thinking of them as irreducibly mental properties. This post, taking for granted this irreducibility, focuses on the question whether it is coherent to suppose that a mental property could be had by a physical substance. Before proceeding, I will note that it is not just qualia, but also the phenomena of intentionality that supply us with putative mental properties. Recalling as I am right now a particular dark and rainy night in Charlottesville, Virginia, I am in an intentional state. So one can reasonably speak of my now instantiating an intentional mental property.

In sum, there are (instantiated) mental properties and there are (instantiated) physical properties, and the former are irreducible to the latter.

2. Now could a physical thing such as a (functioning) brain, or a part thereof, be the possessor of a mental property? Finding this incoherent, I suggest that if there are instantiated mental properties, then there are irreducibly mental subjects. Or perhaps you prefer the contrapositive: If there are no irreducibly mental subjects, then there are no irreducibly mental properties. But it all depends on what exactly we mean by mental and physical properties.

3. What is a physical property? An example is the property of weighing 10 kg. Although there are plenty of things that weigh 10 kg, the property of weighing 10 kg does not itself weigh 10 kg. Physical properties are not themselves physical. So in what sense are physical properties 'physical'? It seems we must say that physical properties are physical in virtue of being properties of physical items. And what would the latter be? Well, tables and chairs, and their parts, and their parts, all the way down to celluose molecules, and their atomic parts, and so on, together with the fields and forces pertaining to them, with chemistry and physics being the ultimate authorities as to what exactly counts as physical.

So I'm not saying that a physical property is a property of a physical thing where a physical thing is a thing having physical properties. That would be circular. I am saying that a physical property is a property of a physical item where physical items are (i) obvious meso- and macro-particulars such as tables and turnips and planets, and (ii) the much less obvious micro-particulars that natural science tells us all these things are ultimately made of. Taking a stab at a definition:

D1. P is a physical property =df P is such that, if it is instantiated, then it is instantiated by a physical item.

Admirably latitudinarian, this definition allows a property to be physical even if no actual item possesses it. This is is as it should be.

4. Now if a physical property is a property of physical items, then a mental property is a property of mental items. After all, no mental property is itself a mind. No mental property feels anything, or thinks about any thing or wants anything. Just as no physical property is a body, no mental property is a mind. So, in parallel with (D1), we have

D2. P is a mental property =df P is such that, if it is instantiated, then it is instantiated by a mental item.

(D2) implies that if there are any instantiated mental properties, there there are irreducibly mental items, i.e., minds or mental subjects. Now there are instantiated mental properties. Therefore, there are irreducibly mental subjects. For all I have shown, these subjects might be momentary entities, hence not substances in the full sense of the term, where this implies being a continuant. The main point, however, is that what instantiates mental properties must be irreducibly mental and so cannot be physical. Therefore, brains could not have mental properties.

This flies in the face of much current opinion. So let's think about it some more. If you countenance irreducibly mental properties being instantiated by brains, do you also countenance irreducibly physical properties being instantiated by nonphysical items such as minds or abstracta? Do you consider it an open question whether some numbers have mass, density, velocity? How fast, and in what direction, is that mathematical function moving? If physical properties cannot be instantiated by nonphysical items, but mental properties can be instantited by nonmental items, then we are owed an explanation of this asymmetry. It is difficult to see what that explanation could be.

Conclusion

5. My argument, then, is this:

a) If there are any instantiated mental properties, then there are irreducibly mental subjects.

b) There are some instantiated mental properties.

Therefore

c) There are irreducibly mental subjects.

(a) rests on (D2).

The attempt to combine property dualism with substance monism is a failure. If all substances are physical, then all properties of these substances are physical. If, on the other hand, there are both mental and physical properties, then there must be both mental and physical subjects, if not substances. A physical item can no more instantiate a mental property than a mental item can instantiate a physical property.

Hi Bill,

Long time reader, first time commenter. I’ve debated the same with some aquaintances who on most cases opt for a physicalist or materialist account of the Mind. After some back and forth, one of these considered (which is quite a lot!) that maybe Neutral Monism could avoid the problems of Dualism (Interaction, the lack of evidence of any disembodied Mind) and of Physicalism (emergence, intentional states), offering a Identity Theory of the Mind whereby brains and its processes are both neutral and we describe some of it’s behaviours as Physical and some as Mental.

I’ve never come across a serious discussion regarding Neutral Monism and its relationship with issues in Philosophy of the Mind. Do you think that NM could bridge the gulf between the two states you propose?

Hope all is well.

I think the property dualist would complain that your definitions stack the deck against him. He would say: I don’t define physical that way. He might give disjunctive analyses:

D3. P is a physical property =df P is a spatial property, or mass, or velocity, etc.

D4. P is a mental property =df P is a quale, or an intentional relation, or etc.

In other words, he would pick out mental/physical properties directly, with reference to their nature, rather than with reference to paradigm particulars.

And even if he accepted your definitions he could surely rephrase his claims accordingly. He could say: Okay, let’s forget about mental/physical particulars. Put my claim this way: The particular (or collection of particulars) that we call the brain also instatiates qualia, intentional relations, etc. Thus making no reference to mental or physical properties.

And I don’t follow this quote: “The main point, however, is that what instantiates mental properties must be irreducibly mental and so cannot be physical.” Surely the property dualist’s claim is that some objects are both irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical? I think you need the additional claim that a mental item cannot also be a physical item.

PS. Your Google sidebar has “example.typepad.com” as the site to search. I don’t think that would be very interesting. I’d much rather search “maverickphilosopher.typepad.com”.

C. Torres,

Thanks for reading. Here is a serious discussion of neutral monism: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neutral-monism/#3.1

Hi Bill,

There is an appealing symmetry to your assertion that “if a physical property is a property of physical items, then a mental property is a property of mental items” — but is it anything more than an appeal to intuition? After all, in contrast to the welter of physical properties we can observe in the world, the only examples we have of mental properties seem always to be intimately associated with a particular physical system, namely the human brain.

Suppose we say this instead: that what you are referring to here as ‘mental’ properties are in fact a special class of physical properties of the living brain, part of the set that includes its weight, temperature, volume, and so on. (As you point out, physical properties are not themselves physical.) This special class of properties differs from more mundane physical properties only in that they are properties that can only be “seen”, from the “inside”, by whatever phsyical system actually instantiates them — and most physical systems don’t.

Instead of parsing out ‘physical’ and ‘mental’ properties, then, perhaps we should instead distinguish between “objective” and “subjective” properties — with subjective properties being how a suitably configured physical system (i.e., one that meets whatever the mechanical, chemical, dynamic, or whatever other yet-to-be-discovered requirements there may be for giving rise to consciousness) experiences itself.

Matt,

Thanks for addressing the substance of my post.

If a physical property is a spatial property, then the problem arises once again: what is a spatial property given that spatial properties are not in space?

As for definition by enumeration of examples, that doesn’t tell us what it is to be a physical property. Suppose someone wanted a definition of ‘prominent 20th century philosopher’ and someone supplied a long enumeration: Russell or Wittgenstein or Heidegger or Sarte or Quine or . . . . That would leave the person in the dark as to the intension of the definiendum.

The same goes for an extensional definition by enumeration of ‘mental property.’ One wouldn’t learn much from a definition that went: the property of wanting a sloop or the property of wanting a purple sloop or the property of fearing a pit bull or the property of believing that some pit bulls have one eye or the property of being in pain or . . .

>>In other words, he would pick out mental/physical properties directly, with reference to their nature, rather than with reference to paradigm particulars.<< But what is that nature? How can I pick out a mental property without some notion of what a mental property is? >> I think you need the additional claim that a mental item cannot also be a physical item.<< That' implicit in what I am saying. After all, the property dualist who believes in mental properties obviously considers them irreducible to physical properties else her would not be a dualist! My point is that what makes a mental property mental as opposed to physical is its being a property of a mental as opposed to a physical item. So I persist in my view that it is incoherent to think that something physical could have mental properties. Let me ask you this: Could something mental have physical properties? If not why not? Could something 'abstract' such as a number or a Fregean proposition have physical properties? If not, why not?

I installed two search engines. The one at the top of the right side bar is for searching MavPhil. The Google engine has two buttons. One for searching the Web. I can’t figure out how to change the default setting of the other, which I want also to search MavPhil.

Bill,

“If a physical property is a spatial property, then the problem arises once again: what is a spatial property given that spatial properties are not in space?”

But I think this is where things bottom out. What is redness? It’s, well, red. I think the same hold for spatial relations: you just know them when you see them.

But I don’t I think endorse the claim that a property is physical iff it is spatial. My monitor sense-datum is currently above my desk sense-datum. Does it follow that sense-data are physical? I don’t think so, but I’m not really sure.

“One wouldn’t learn much from a definition that went: the property of wanting a sloop or the property of wanting a purple sloop or the property of fearing a pit bull or the property of believing that some pit bulls have one eye or the property of being in pain or . . .”

Well, alright. But how about this definition of mental:

D5 P is a mental property =df P is either a quale or an intentional relation.

This includes everything in your list. Does it include everything mental?

“But what is that nature? How can I pick out a mental property without some notion of what a mental property is?”

What I said was admittedly ambiguous. I meant “with reference to their individual nature” not “with reference to their common nature”.

But as for common nature, maybe ‘mental’ and ‘physical’ deserve the same treatment that Wittgenstein gave ‘game’. (I can’t remember the technical term he used.)

“That’s implicit in what I am saying. After all, the property dualist who believes in mental properties obviously considers them irreducible to physical properties else he would not be a dualist!”

I think you misread me. Rephrasing your definitions to avoid the appearance of circularity, you say:

D1′. P is a physical property =df P is such that, if it is instantiated, then it is instantiated by A, B, C (where these are paradigm cases).

D2′. P is a mental property =df P is such that, if it is instantiated, then it is instantiated by X, Y, Z (paradigm mental cases).

My point was that this does nothing to rule out

1) A = Z, B = Y & C = Z.

In fact, if that did happen, then it would entail the identity of mental/physical properties. So one problem with your view is this: it can draw no distinction between identity theory and panpsychism. The latter holds that mental/physical properties are irreducible but always go together. On your analysis this view cannot be coherently stated.

“Let me ask you this: Could something mental have physical properties? If not why not? Could something ‘abstract’ such as a number or a Fregean proposition have physical properties? If not, why not?”

Okay, this looks like a separate argument. As to the former, I gave the example of sense-data above. As to the latter, I’m very much inclined to agree, although I’m not sure why. Perhaps because they are universals?

Malcolm,

You are missing the point that this post presupposes a dualism of properties in order to pursue the question: Can substance monism be coherently combined with property dualism? That’s the issue.

Matt,

‘Mental’ is ambiguous. A sense datum is mental but it is not a mind. A mind is mental but it is a mind. So I’ll rephrase my question to you: Could a mind whether embodied or not have physical properties? For example, could God or an angel have physical properties?

I think you will say that God, a pure spirit, cannot have physical properties. Now ask yourself why you think this. Isn’t it because anything that has physical properties must be physical? To say that that a pure spirit has physical properties such as identity, mass, etc. smacks of a category mistake.

Do you buy that? Well,then, by parity of reasoning, purely physical things such as brains cannot have mental properties. Which is my point.

My definitions leave something to be desired. What I want to say is that the sense of ‘physical’ in ‘physical property’ has to come from elsewhere — because physical properties are not themselves physical. So I ask: in relation to what is a physical property called physical? My answer: Physical properties are called physical because they are the properties of physical things. So it is part of the very sense of ‘physical property’ that only physical particulars can instantiate such properties. If so, it is part of the very sense of ‘mental property’ that only mental particulars (minds) can instantiate mental properties.

Have I convinced you?

Bill,

“You are missing the point that this post presupposes a dualism of properties…”

Am I? I thought that what I was questioning, if admittedly somewhat digressively after my first paragraph, was only your intuitive appeal to symmetry to argue that if we agree that something mental cannot have physical properties, we should therefore be confident that something physical cannot have mental properties.

I think the parity argument you are offering is right, Bill. The principle that (non-)physical properties must belong to (non-)physical substances seems axiomatic to me and quite plausible, although it admittedly is not as luminously clear to the intellect as other axioms (e.g., ~(A & ~A)).

Someone may respond to your parity argument with: “I am not yet convinced that a physical substance cannot have non-physical properties.” What can we say to such a person except that he continue to think over it until it becomes clear in his mind? It’s hardly convincing at the moment, and such a response won’t win any public debates, but there are many dicta that, though initially they seem opaque and uncertain and subject to counterexample, yet later they appear as obvious and undeniable.

Bill,

“I think you will say that God, a pure spirit, cannot have physical properties. Now ask yourself why you think this. Isn’t it because anything that has physical properties must be physical?”

I’m not sure I buy that God doesn’t have physical properties. The attribute of omnipresence can be construed in such a way that God is at every location. I agree that if anything has physical properties it is physical, but I don’t view ‘being physical’ and ‘being mental’ as mutually exclusive categories at the level of the particular.

“I ask: in relation to what is a physical property called physical? My answer: Physical properties are called physical because they are the properties of physical things.”

I think the problem with this is that on the surface it looks circular, and when you eliminate that appearance the sentence immediately following the quoted sentence doesn’t follow. All you intend by “physical things” must be the denotation of certain paradigm cases. But I think I agree with you that no hard and fast definition can be given of ‘physical’. I think I would define physical property as the sort of property you encounter in physics textbooks and go from there. (I proposed a definition of mental property above). But I can’t think of any way to move from that to ‘if a particular instantiates a physical property, then it can only instantiate physical properties’, so you haven’t convinced me in that respect.

Matt,

>>I agree that if anything has physical properties it is physical, but I don’t view ‘being physical’ and ‘being mental’ as mutually exclusive categories at the level of the particular.<< This suggests the following. There are physical properties. They are irreducible to mental properties. If anything has a physical property, then it too is irreducibly physical. There are mental properties. They are irreducible to physical properties. But it is not the case that if anything has a mental property, then it is irreducibly mental. This is a Non-Parity position in which the primacy is given to the physical. Now, two questions. Can you argue for your Non-Parity position? Can you give good reasons why someone should not give a Non-Parity position in which the mental has primacy?

Steven,

Yes, in the end, you just say to your opponent: what you’re proposing (non-parity) makes no sense, you only think it does. But that’s in the end; before we get to the end we should look for arguments.

Bill,

Ah, no. I must not have been very clear. All of your first paragraph I agree with except for the last sentence. If something has both mental and physical properties then I think it is both irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical. After all, it has irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical properties.

Steven,

You say, “The principle that (non-)physical properties must belong to (non-)physical substances seems axiomatic to me and quite plausible”.

My problem is I can’t see any way of characterising a physical substance save with reference to the sort of properties it instantiates. So on my reading your proposed axiom is analytically true, but I don’t think that is the sense in which you intend it. Moreover, your principle is perfectly compatible (as I pointed out to Bill earlier) with a physical substance being identical to a non-physical substance. On what grounds would you rule that out?

Matt sez: >>Ah, no. I must not have been very clear. All of your first paragraph I agree with except for the last sentence. If something has both mental and physical properties then I think it is both irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical. After all, it has irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical properties.<< Sorry, but that strikes me as utterly absurd. Consider a sensory quale such as the sensation of red. That, you will agree, is irreducible to any brain state (or any physical state. The property dualist will say that it is a feature or property of some portion of Mary's brain. (Frank Jackson's Mary has just emerged from her black-and-white prison and is looking at a red rose.) So what you are saying is that that portion of Mary's brain is both irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical. But that's a contradiction: nothing can be both. It is also not what the property dualist is maintaining. He's a naturalist and thus a substance monist. The brain is wholly physical, exhaustively understandable in terms of physics, chemistry, electro-chemistry, etc. And yet the brain is that which instantiates mental properties. The theory is that one and the same item, which is wholly physical yet instantiates both irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical properties. Your argument is a non sequitur. Why can't something that has both irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical properties be irreducibly physical but only reducibly mental? I don't think you understand what the property dualist is saying. Either that, or I don't understand.

Bill,

“So what you are saying is that that portion of Mary’s brain is both irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical. But that’s a contradiction: nothing can be both.”

As I see it, this simply begs the question against the property dualist, since that it precisely what he is claiming. What are your reasons for thinking that something cannot be both? It isn’t a logical contradiction. Your reasons must presumably come from an analysis of what it is for a particular to be irreducibly x. But I don’t see that you have done the necessary spadework in this regard.

“The theory is that one and the same item, which is wholly physical yet instantiates both irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical properties.”

Your understanding of property dualism is indeed different from mine. In fact, I struggle to make sense of the doctrine as you state it. How can something be wholly physical and yet possess irreducible mental properties? If something is wholly physical then surely this has to mean that all its (intrinsic?) properties are at bottom physical properties? But then there is no room for the irreducibly mental.

Here is how I would state property dualism:

1) There are mental properties.

2) There are physical properties.

3) No mental property is identical to any physical property.

4) Possibly, some particular instantiates a mental property and a physical property.

Does this help?

Matt,

A particular (whether a portion of a brain, a brain event, a brain process, etc.) is irreducibly mental iff it is mental but not physical. A particular is irreducibly physical iff it is physical but not mental. To say that x is irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical is to say that x is mental but not physical and physical but not mental. But this entails two contradictions. First, that x is mental and x is not mental. Second, that x is physical and x is not physical.

Do you accept the Law of Non-Contradiction? If yes, then your view is contradictory twice over.

Do you agree?

>>Here is how I would state property dualism:

1) There are mental properties.

2) There are physical properties.

3) No mental property is identical to any physical property.

4) Possibly, some particular instantiates a mental property and a physical property.<< You need to state that the particular mentioned in (4) is a brain or a portion of a brain or a brain state or event or process. For if that particular were a Cartesian ego, then you would be describing a position that no one currently discusses. Property dualism in the philosophy of mind goes together with substance monism where all the substances are physical. Yes or no?

Here’s a modified version:

1) There are mental properties.

2) There are physical properties.

3) All properties must be instantiated by an object or objects.

4) No mental property is identical to any physical property.

5) Some objects have only physical properties.

6) All objects with mental properties must also have certain other physical properties.

William,

Your version seems to allow a Cartesian ego that has both mental and physical properties. Do you want to allow that?

Bill,

“A particular (whether a portion of a brain, a brain event, a brain process, etc.) is irreducibly mental iff it is mental but not physical.”

Okay, but this isn’t how I would characterise ‘being irreducibly mental’. I would say a particular is irreducibly mental iff it instantiates a property that is mental and that property is not identical to any physical property. So I disagree that I have contradicted myself according to how I use the term ‘irreducibly’ of particulars.

“Property dualism in the philosophy of mind goes together with substance monism where all the substances are physical. Yes or no?”

I think so – I’m not sure how to parse ‘substance monism’. But I agree that a lot of the naturalistically inclined property dualists will say that all substances are physical substances. But all I read them as claiming there is that every substance will instantiate at least one physical property.

I think our understanding of the terms is different.

”

Your version seems to allow a Cartesian ego that has both mental and physical properties. Do you want to allow that?

”

Point 6) would be empirically established, so why not, if such a thing can be empirically found?

This, perhaps?

1) There are mental properties.

2) There are physical properties.

3) All properties must be instantiated by an object or objects.

4) No mental property is identical to any physical property.

5) Only physical objects have physical properties.

6) Some physical objects have mental properties.

7) All objects with mental properties must also have certain other physical properties.

Matt,

I concede that you are not contradicting yourself. You have extricated yourself admirably!

Of course you don’t want to say that the brain has mental properties in virtue of an immaterial part of the brain having mental properties. Do you want to say

a) the brain, since it has both kinds of properties, is both mental and physical and therefore not simply physical

or

b) the brain, though simply physical, has both kinds of properties?

Malcolm,

That does the trick. That is fair summary of what contemporary property dualists maintain.

As for the choices above, b) is certainly what I have always property dualism to mean. Wouldn’t a) be substance dualism?

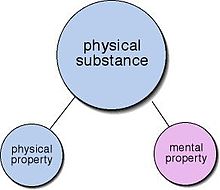

The brief Wikipedia entry on Property Dualism offers this diagram, for what it’s worth:

“…always understood property dualism to mean,” I meant to say.

I’m unclear what type of property patterns are considered for this discussion. For example, you see fur stones in a straight line. Is “being in a straight line” a physical property of the collection of the stones? Would properties of collections be a different type of property than properties of stones?

Do insects have any mental properties? When a bee does a dance that shows other bees where there is a new hive, and describes it, is there anything mental there?

Bill,

(a) is what I took property dualism to mean, not (b). (I myself am a substance dualist.) Contra Pollack, I don’t think (a) amounts to substance dualism, though it does include some forms of it. Cartesian dualism at any rate is excluded because it restricts extension to the physical and thought to the mental. So if you instantiate a mental property you are excluded from instantiating a physical one, but that commitment is ruled out by (a).

So I guess I was wrong about how property dualists want to characterise themselves. But now I’m not too sure what they are trying to say. How can they justify their claim that eg. the brain is nevertheless a physical substance, not a mental substance, despite it instantiating both types of property?

In terms of Pollack’s diagram: surely the only reason the big circle can be considered blue is because of the little blue circle it is connected to. But if the big circle is blue due to its connection to the little blue circle, then it should also, by parity of reasoning, be considered pink by virtue of its connection to little pink circle. So I want to colour half of the big circle pink and the other half blue. For how can a substance be characterised as physical except by virtue of the properties it instantiates?

Although maybe this is what the property dualist wants to say: Being a physical substance does indeed involve instantiating a lot of physical properties (denoted by the big circle). But there are still other inessential physical properties such a substance will instantiate, as well as mental properties if it is a brain. It is these which are denoted by the smaller circles. Furthermore, these smaller circles are to be considered as properties of the instantiation of the properties denoted by the big circle, not as properties of the particular which instantiates the properties denoted by the big circle.

I concede that this scheme would grant the ontological priority of the physical. Is this a fair way of reading the property dualist’s claims?

Matt,

I’ll confess, then, that I’m having some trouble understanding the distinction between what Bill excluded when he said that “Of course you don’t want to say that the brain has mental properties in virtue of an immaterial part of the brain having mental properties“, and what is meant by the brain being “both mental and physical”.

What does it mean to say something “is both mental and physical” if not that it comprises both kinds of substance? And if so, isn’t that the same as having a physical part and an “immaterial part”? (Saying the brain is “both mental and physical” is different from saying it is neither, as I understand neutral monism to say.)

Perhaps what is meant by “both mental and physical” is only to say that it instantiates both kinds of properties. But doesn’t that then collapse into b)?

Also, I’m puzzled as to why “these smaller circles are to be considered as properties of the instantiation of the properties denoted by the big circle, not as properties of the particular which instantiates the properties denoted by the big circle.” I would think that the materialist property dualist would just say that all the properties of the brain, both physical and mental, are directly instantiated by the physical substance of the brain. Why the middleman?

This does mean that the property dualist would have to reject the parity-of-reasoning argument. But given that the only mental properties we have ever had any knowledge of appear to be instantiated only where there are physical brains, and nowhere else, why should we find the parity argument compelling with regard to mental properties?

Also, regarding the parity argument: the property “is foolish” can be instantiated by both a mental particular, as in “narcissism is foolish”, and by a physical particular, as in “Kim Kardashian is foolish”. If a single property can be instantiated by multiple types of particulars, why should we be confident that multiple types of properties can’t be instantiated by a single particular?

You asked: “For how can a substance be characterised as physical except by virtue of the properties it instantiates?” I suppose the easy way out is simply to say that if a substance instantiates physical properties, it’s physical, period — or even to assert that physical substance (which in some special cases instantiates mental properties) is in fact the only kind of substance there is.

Matt,

You are coming to appreciate what it was that bothered me about property dualism in the first place, namely, how can a physical thing such as brain instantiate a mental property?

>> How can they justify their claim that eg. the brain is nevertheless a physical substance, not a mental substance, despite it instantiating both types of property?<< That's exactly my problem with property dualism.

Gentlemen,

I made this distinction:

a) the brain, since it has both kinds of properties, is both mental and physical and therefore not simply physical

or

b) the brain, though simply physical, has both kinds of properties?

The fact that Matt plumps for (a) and Malcolm for (b) shows that there is a problem as to what exactly property dualism is. The official line, I take it, is (b). There is exactly one substance or individual thing, the brain, but it has both irreducibly mental and irreducibly physical properties. Moreover, this is the brain as contemporary neuroscience understands it. There is no special part of the bain that instantiates mental properties. That would go against the materia;list/naturalist thrust of property dualism.

I agree with Malcom as to what property dualism officially is. But I agree with Matt that the official line doesn’t make much sense.

But this is tricky stuff. Consider a more mundane example. Color properties cannot be reduced to shape properties, e.g. redness to sphericity. But here is a red ball. It instantiates a color property and a shape property. Is that a problem? Apparently not. (Note that it is not different parts of the ball that instantiate the different properties.) So why can’t a brain have both physical and mental properties?

I don’t think this analogy works. I’ll give my reasons later.