That philosophers disagree is a fact about which there is little disagreement, even among philosophers. But what this widespread and deep disagreement signifies is a topic of major disagreement. One issue is whether or not the fact of disagreement supplies a good reason to doubt the possibility of philosophical knowledge.

That philosophers disagree is a fact about which there is little disagreement, even among philosophers. But what this widespread and deep disagreement signifies is a topic of major disagreement. One issue is whether or not the fact of disagreement supplies a good reason to doubt the possibility of philosophical knowledge.

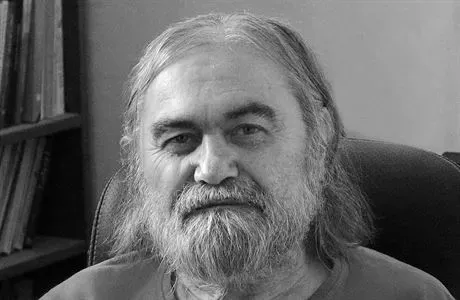

The contemporary Czech philosopher Jiří Fuchs begins his book Illusions of Sceptics (2016) by considering this question. He grants that the "cognitive potential of philosophy" is called into question by the "embarrassing fact that there is not a single thing that philosophers would agree on." (13) Nevertheless, Fuchs insists that we have no good reason to be skeptical about the possibility of philosophical knowledge. His view is that "Discord among philosophers can . . . be sufficiently explained by the frequent prejudices of philosophers . . . Consequently, the existence of discord among philosophers does not imply that their work is of fundamentally unscientific character." (16)

Besides the prejudices of philosophers, the lack of consensus among philosophers may also be attributed to philosophy's difficulty: "the discord may just be a consequence of the specific challenging character of philosophy."(19)

Fuchs maintains that "consensus has no relation to the core of scientific quality. . . ." (24). The core of scientific quality is constituted by "proof or demonstration." (24) His claim is that interminable and widespread disagreement or lack of consensus has no tendency to show that philosophy is incapable of achieving genuine knowledge, where such knowledge involves apodictic insight into the truth of some philosophical propositions.

There are two main issues we need to discuss. One concerns the relation of consensus and truth; the other the relation of consensus and knowledge. My impression is that Fuchs conflates the two issues. I will argue, contra Fuchs, that while it is obvious that consensus and truth are logically independent, it is not obvious that consensus and knowledge are logically independent. My view, tentatively held, is that the lack of consensus in philosophy does tend to undermine philosophy's claim to be knowledge.

Consensus and Truth

I maintain, and Fuchs will agree, that the following propositions are true if not platitudinous.

1) Truth does not entail consensus. If a proposition is true, it is true whether or not there is consensus with respect to its truth.

2) Consensus does not entail truth. If most or all experts agree that p, it does not follow that p is true.

3) Consensus and truth are logically independent. This follows from (1) in conjunction with (2). One can have truth without consensus and consensus without truth.

Lack of consensus, therefore, does not demonstrate lack of truth. Even if no philosophical proposition wins the agreement of a majority of competent practitioners, it is possible that some such propositions are true. But it doesn't follow that some philosophical propositions have 'scientific quality.' To have this quality they have to be true, but they also have to be knowable by us. But what is knowability and how does it relate to consensus? To answer this question we must first clarify some other notions.

Truth, Knowledge, Knowability, Cognitivity, Justification, and Certainty

I add to our growing list the following propositions, perhaps not all platitudinous and perhaps not all agreeable to Fuchs:

4) Knowledge entails truth. If S knows that p, it follows that p is true. There is no false knowledge. There are false beliefs, and indeed justified false beliefs; but there is no false knowledge. You could think of this as an conceptual truth, or as a truth about the essence of knowledge. These are different because a concept is not the same as an essence.

5) Truth does not entail knowledge. If p is true, it does not follow that someone (some finite mind or ectypal intellect) knows that p. If an omniscient being, an archetypal intellect, exists, then of course every true proposition p is known by the omniscient being.

6) Truth does not entail knowability by us. If, for any proposition p, p is true, it does not follow that there is any finite subject S such that S has the power to know p. There may be truths which, though knowable 'in principle,' or knowable by the archetypal intellect, are not knowable by us.

7) Cognitivity does not entail knowability. Let us say that a proposition is cognitive just in case it has a truth value. Assuming bivalence, a proposition is cognitive if and only if it is either true, or if not true, then false. Clearly, cognitivity is insufficient for knowability. For if a proposition is false, then it is cognitive but cannot be known because it is false. And if a proposition is true, then it is cognitive but may not be knowable because beyond our ken.

8) Knowledge entails justification. If S believes that p, and p is true, it does not follow that S knows that p. For knowledge, justification is also required. This is a bit of epistemological boilerplate that dates back to Plato's Theaetetus.

9) Knowledge entails objective certainty. Knowledge implies the sure possession, by the subject of knowledge, the knower, of the object of knowledge; if the subject is uncertain, then the subject does not have knowledge strictly speaking. Objective certainty is not to be confused with subjective certitude.

Consensus and Knowledge

Fuchs and I will agree that consensus is not necessary for truth: a true proposition need not be one that enjoys the consensus of experts. But consensus may well be necessary for knowledge. Fuchs, however, seems to conflate truth and certainty, and thus truth with knowledge. A truth can be true without being known by us; indeed, without even being knowable by us. But, necessarily, whatever is known is true. On p. 30 we read:

By denying that the thought processes of philosophers can exhibit a scientific quality simply because of the existence of discord among philosophers, we make consensus a necessary condition for the general validity and potential certainty of scientific knowledge, which is the attribute of science. (Emphasis added.)

On the following page we find the same thought but with a replacement of 'potential certainty' by 'certainty':

. . . the necessary question of whether the consensus of experts is really such an essential and indispensable condition for the certainty and general validity of scientific knowledge. (31, emphasis added.)

When one speaks of the validity of a proposition, one means its truth. ('Valid' as a terminus technicus in formal logic is not in play here.) So it seems clear that Fuchs is maintaining that consensus is necessary neither for the truth of propositions nor for their certainty. He seems to be maintaining that one can have certain knowledge of a proposition even if the consensus of experts goes against one. This is not obvious. Why not?

Knowledge requires justification. Now suppose I accept the proposition that God exists and that my justification takes the form of various arguments for the existence of God. Those arguments will be faulted by an army of competent practitioners, not all of them atheists, on a variety of grounds. What's more, the members of the atheist divisions will marshal their own positive arguments, the strongest of them being arguments from evil. Now if just one of my theistic arguments is sound, then God exists.

But I do not, by giving a sound argument for God, know that God exists unless I know that the argument I have given is sound. (A sound argument is a valid deductive argument all of the premises of which are true.) But how do I know that even one of my theistic arguments is sound? How can I legitimately claim to know that when a chorus of my epistemic peers rises up against me?

If what I maintain is true, then it is true no matter how many epistemic peers oppose me: they are just wrong! Truth is absolute: it is not sensitive to the vagaries of agreement and disagreement. Justification, however, is sensitive to agreement and disagreement. My justification for considering a certain argument sound is undermined by your disagreement assuming that we are both competent in the subject matter of the argument and we are epistemic peers.

In a situation in which my justification for believing that p is undermined by the disagreement of competent peers, there is no objective certainty that p. If knowledge logically requires objective certainty, and objective certainty is destroyed by the disagreement of competent epistemic peers, then I can no longer legitimately claim to know that p. So, while truth has nothing to fear from lack of agreement, knowledge does. For knowledge requires justification, and justification can be augmented or diminished by agreement or disagreement, respectively.

Interim Conclusion

Fuchs makes things too easy for himself by conflating truth and knowledge. We can agree that consensus is logically irrelevant to truth. Protracted disagreement by the (morally) best and the (intellectually) brightest over the truth value of some proposition p has no tendency to show either deductively or inductively that p is not either true or false. Truth is absolute by its very nature and thus insulated from the vagaries of opinion. But truths (true propositions) do not do us any good unless we can know them. It is not enough to know that some truths are known; what we need is to know of a given truth that it is true. But disagreement inserts a skeptical blade between the truth and our knowledge of it.

Disagreement in philosophy undermines her claims to knowledge. As I see it, Fuchs has done nothing to undermine this undermining.