Here is the beginning of the letter he sent me:

I've been considering converting to Islam.

You've had a big part in this, though I know it won't please you to hear it. Your arguments against the coherency of the Incarnation are hard to get past.

My arguments against the Chalcedonian, 'two-natures-one-person' theology of the Incarnation may or may not have merit. In any case, this is not the place to rehearse or defend them. What I want to say to my young reader is that it would be a mistake to reject Christianity because of the problems of the Trinitarian-Incarnational version thereof. Someone who rejects Trinity and Incarnation as classically conceived might remain a Christian by becoming a Unitarian. My friend Dale Tuggy represents a version of Unitarianism. You will have no trouble finding his writings on the Web.

There are any number of better choices than Islam if one wants a religion and cannot accept orthodox — miniscule 'o' — Christianity. There is, in addition to Unitarian Christianity, Buddhism, Judaism, Hinduism, all vastly superior to "the saddest and poorest form of theism" (Schopenhauer) . . . .

I will conclude this entry by posting some quotations from William Ellery Channing, the 19th century American Unitarian. These are from Unitarian Christianity (1819). (HT: Dave Bagwill) Bolding added.

In the first place, we believe in the doctrine of God's UNITY, or that there is one God, and one only. To this truth we give infinite importance, and we feel ourselves bound to take heed, lest any man spoil us of it by vain philosophy. The proposition, that there is one God, seems to us exceedingly plain. We understand by it, that there is one being, one mind, one person, one intelligent agent, and one only, to whom underived and infinite perfection and dominion belong. We conceive, that these words could have conveyed no other meaning to the simple and uncultivated people who were set apart to be the depositaries of this great truth, and who were utterly incapable of understanding those hair- breadth distinctions between being and person [substance and supposit?], which the sagacity of later ages has discovered. We find no intimation, that this language was to be taken in an unusual sense, or that God's unity was a quite different thing from the oneness of other intelligent beings.

We note here a similarity to Islam: "There is no god but God."

We also note that unity is defined in terms of 'one' taken in an ordinary numerical way. Reading the above and the sequel I am struck at how similar this is to the way Tuggy thinks. God is a being among beings, and his unity is no different than the unity of Socrates. There are of course many men, and Socrates is but one of them. But if Socrates were the only man, then he would be the one man in the way God is the one god. Unity in classical Christianity has a deeper meaning: God is not just numerically one; he is also one in a way nothing else is one. God is not the sole instance of deity; God is his deity; God does not have (instantiate) his attributes; he is his attributes. God is not only unique, like everything else; he is uniquely unique unlike anything else. God is not just the sole instance of his kind; he is unique in the further sense that there is no real distinction in God between instance and kind.

We object to the doctrine of the Trinity, that, whilst acknowledging in words, it subverts in effect, the unity of God. According to this doctrine, there are three infinite and equal persons, possessing supreme divinity, called the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Each of these persons, as described by theologians, has his own particular consciousness, will, and perceptions. They love each other, converse with each other, and delight in each other's society. They perform different parts in man's redemption, each having his appropriate office, and neither doing the work of the other. The Son is mediator and not the Father. The Father sends the Son, and is not himself sent; nor is he conscious, like the Son, of taking flesh. Here, then, we have three intelligent agents, possessed of different consciousness[es], different wills, and different perceptions, performing different acts, and sustaining different relations; and if these things do not imply and constitute three minds or beings, we are utterly at a loss to know how three minds or beings are to be formed. It is difference of properties, and acts, and consciousness, which leads us to the belief of different intelligent beings, and, if this mark fails us, our whole knowledge fall; we have no proof, that all the agents and persons in the universe are not one and the same mind. When we attempt to conceive of three Gods, we can do nothing more than represent to ourselves three agents, distinguished from each other by similar marks and peculiarities to those which separate the persons of the Trinity; and when common Christians hear these persons spoken of as conversing with each other, loving each other, and performing different acts, how can they help regarding them as different beings, different minds?

For Channing, Trinitarianism is indistinguishable from tri-theism. His too suggests a comparison with Islam. From the point of view of a radical monotheist, Trinitarianism smacks of polytheism.

Having thus given our views of the unity of God, I proceed in the second place to observe, that we believe in the unity of Jesus Christ. We believe that Jesus is one mind, one soul, one being, as truly one as we are, and equally distinct from the one God. We complain of the doctrine of the Trinity, that, not satisfied with making God three beings, it makes; Jesus Christ two beings, and thus introduces infinite confusion into our conceptions of his character. This corruption of Christianity, alike repugnant to common sense and to the general strain of Scripture, is a remarkable proof of the power of a false philosophy in disfiguring the simple truth of Jesus.

According to this doctrine, Jesus Christ, instead of being one mind, one conscious intelligent principle, whom we can understand, consists of two souls, two minds; the one divine, the other human; the one weak, the other almighty; the one ignorant, the other omniscient. Now we maintain, that this is to make Christ two beings. To denominate him one person, one being, and yet to suppose him made up of two minds, infinitely different from each other, is to abuse and confound language, and to throw darkness over all our conceptions of intelligent natures. According to the common doctrine, each of these two minds in Christ has its own consciousness, its own will, its own perceptions. They have, in fact, no common properties. The divine mind feels none of the wants and sorrows of the human, and the human is infinitely removed from the perfection and happiness of the divine. Can you conceive of two beings in the universe more distinct? We have always thought that one person was constituted and distinguished by one consciousness. The doctrine, that one and the same person should have two consciousness, two wills, two souls, infinitely different from each other, this we think an enormous tax on human credulity.

There are closely related difficult questions about how one person or supposit can have two distinct individualized natures, one human and one divine.

And so I say to my young friend, "Don't do anything rash!" First consider whether there is a less deadly form of religion you can adopt that will satisfy your intellectual scruples.

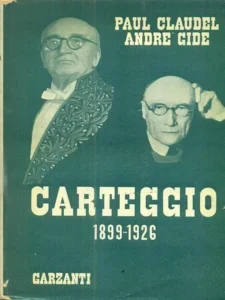

On occasion we encounter morally good people who are sincerely interested in our spiritual welfare, so much so that they fear that we will be lost if we differ from the views they cherish, even if our views are not so very different from theirs. Julian Green in his Diary 1928-1957, entry of 10 April 1929, p. 6, said to André Gide:

On occasion we encounter morally good people who are sincerely interested in our spiritual welfare, so much so that they fear that we will be lost if we differ from the views they cherish, even if our views are not so very different from theirs. Julian Green in his Diary 1928-1957, entry of 10 April 1929, p. 6, said to André Gide: