Andrew C. McCarthy maintains.

Month: January 2015

Bill Maher on Charlie Hebdo

As much of a jackass as Bill Maher can be, I appreciate the cojones and good judgment he displays when he speaks the truth about Islam and terrorism.

More Islamist Thuggery

"A senior Islamic cleric in Ireland has issued a warning against reproducing Charlie Hebdo's front page depiction of the Prophet Muhammad, after the massacre of journalists and police at the magazine's offices." (HT: Karl White)

Leftist Enablers as Useful Idiots

Having lost their heads, they are in danger of losing their heads.

…………..

Addendum 1/9. It is a nice literary question whether the above formulation is superior to

Having lost their minds, they are in danger of losing their heads.

I like both formulations but prefer the first because it exploits an equivocation on 'lose one's head.' Logical heads shun equivocation like the plague, but it has its literary uses and charms.

By the way, the sentence immediately preceding features the figure of speech known as the synecdoche.

What Explains the Left’s Toleration of Militant Islam?

From 1789 on, a defining characteristic of the Left has been hostility to religion, especially in its institutionalized forms. This goes together with a commitment to such Enlightenment values as individual liberty, belief in reason, and equality, including equality among the races and between the sexes. Thus the last thing one would expect from the Left is an alignment with militant Islam given the latter’s philosophically unsophisticated religiosity bordering on rank superstition, its totalitarian moralism, and its opposition to gender equality.

So why is the radical Left soft on militant Islam? The values of the progressive creed are antithetic to those of the Islamists, and it is quite clear that if the Islamists got everything they wanted, namely, the imposition of Islamic law on the entire world, our dear progressives would soon find themselves headless. I don’t imagine that they long to live under Sharia, where ‘getting stoned’ would have more than metaphorical meaning. So what explains this bizarre alignment?

1. One point of similarity between radical leftists and Islamists is that both are totalitarians. As David Horowitz writes in Unholy Alliance: Radical Islam and the American Left (Regnery, 2004) , "Both movements are totalitarian in their desire to extend the revolutionary law into the sphere of private life, and both are exacting in the justice they administer and the loyalty they demand." (p. 124)

2. Horowitz points to another similarity when he writes, "The radical Islamist believes that by conquering nations and instituting sharia, he can redeem the world for Allah. The socialist’s faith is in using state power and violent means to eliminate private property and thereby usher in the millenium." (129)

Perhaps we could say that the utopianism of the Left is a quasi-religion with a sort of secular eschatology. The leftist dreams of an eschaton ushered in by human effort alone, a millenial state that could be described as pie-in-the-future as opposed to pie-in-the-sky. When this millenial state is achieved, religion in its traditional form will disappear. Its narcotic satisfactions will no longer be in demand. Religion is the "sigh of the oppressed creature," (Marx) a sigh that arises within a contingent socioeconomic arrangement that can be overturned. When it is overturned, religion will disappear.

3. This allows us to explain why the secular radical does not take seriously the religious pathology of radical Islam. "The secular radical believes that religion itself is merely an expression of real-world misery, for which capitalist property is ultimately responsible." (129) The overthrow of capitalist America will eliminate the need for religion. This "will liberate Islamic fanatics from the need to be Islamic and fanatic." (130)

Building on Horowitz’s point, I would say the leftist in his naïveté fails to grasp that religion, however we finally resolve the question of its validity or lack thereof, is deeply rooted in human nature. As Schopenhauer points out, man is a metaphysical animal, and religion is one expression of the metaphysical urge. Every temple, church, and mosque is evidence of man's being an animal metaphysicum. As such, religion is not a merely contingent expression of a contingent misery produced by a contingent state of society. On the contrary, as grounded in human nature, religion answers to a misery, sense of abandonment, and need for meaning essential to the human predicament as such, a predicament the amelioration of which cannot be brought about by any merely human effort, whether individual or collective. Whether or not religion can deliver what it promises, it answers to real and ineradicable human needs for meaning and purpose, needs that only a utopian could imagine being satisfied in a state of society brought about by human effort alone.

In their dangerous naïveté, leftists thinks that they can use radical Islam to help destroy the capitalist USA, and, once that is accomplished, radical Islam will ‘wither away.’ But they will ‘wither away’ before Islamo-fanaticism does. They think they can use genuine fascist theocracy to defeat the ‘fascist theocracy’ of the USA. They are deluding themselves.

Residing in their utopian Wolkenskukuheim — a wonderful word I found in Schopenhauer translatable as 'Cloud Cuckoo Land' — radical leftists are wrong about religion, wrong about human nature, wrong about the terrorist threat, wrong about the ‘fascist theocracy’ of conservatives, wrong about economics; in short, they are wrong about reality.

Leftists are delusional reality-deniers. Now that they are in our government, we are in grave danger. I sincerely hope that people do not need a 'nuclear event' to wake them up. Political Correctness can get you killed.

A Dog Named ‘Muhammad’

There is a sleazy singer who calls herself 'Madonna.' That moniker is offensive to many. But we in the West are tolerant, perhaps excessively so, and we tolerate the singer, her name, and her antics. Muslims need to understand the premium we place on toleration if they want to live among us.

A San Juan Capistrano councilman named his dog 'Muhammad' and mentioned the fact in public. Certain Muslim groups took offense and demanded an apology. The councilman should stand firm. One owes no apology to the hypersensitive and inappropriately sensitive. We must exercise our free speech rights if we want to keep them. Use 'em or lose 'em.

The notion that dogs are 'unclean' is a silly one. So if some Muslims are offended by some guy's naming his dog 'Muhammad,' their being offended is not something we should validate. Their being offended is their problem.

Am I saying that we should act in ways that we know are offensive to others? Of course not. We should be kind to our fellow mortals whenever possible. But sometimes principles are at stake and they must be defended. Truth and principle trump feelings. Free speech is one such principle. I exercised it when I wrote that the notion that dogs are 'unclean' is a silly one.

Some will be offended by that. I say their being offended is their problem. What I said is true. They are free to explain why dogs are 'unclean' and I wish them the best of luck. But equally, I am free to label them fools.

With some people being conciliatory is a mistake. They interpret your conciliation and willingness to compromise as weakness. These people need to be opposed vigorously. For the councilman to apologize would be foolish.

Language and Reality

London Ed sends his thoughts on language and reality. My comments are in blue.

Still mulling over the relation between language and reality. Train of thought below. I tried to convert it to an aporetic polyad, but failed. The tension is between the idea that propositions are (1) mind-dependent and (2) have parts and so (3) have parts that are mind-dependent. Yet (if direct reference is true) some of the parts (namely the parts corresponding to genuinely singular terms) cannot be mind-dependent.

How about this aporetic hexad:

1. Propositions are mind-dependent entities.

2. Atomic (molecular) propositions are composed of sub-propositional (propositional) parts.

3. If propositions are mind-dependent, then so are its parts.

4. In the case of genuine singular terms (paradigm examples of which are pure indexicals), reference is direct and not mediated by sense.

5. If reference is direct, then the meaning of the singular referring term is exhausted by the term's denotatum so that a proposition expressed by the tokening of a sentence containing the singular referring term (e.g, the sentence 'I am hungry') has the denotatum itself as a constituent.

6. In typical cases, the denotatum is a mind-independent item.

Note that (3) is not an instance of the Fallacy of Division since (3) is not a telescoped argument but merely a conditional statement. London Ed, however, may have succumbed to the fallacy above. Or maybe not.

Our aporetic hexad is a nice little puzzle since each limb is plausible even apart from the arguments that can be given for each of them.

And yet the limbs of this hexad cannot all be true. Consider the proposition BV expresses when he utters, thoughtfully and sincerely, a token of 'I am hungry' or 'Ich bin hungrig.' By (4) in conjunction with (5), BV himself, all 190 lbs of him, is a proper part of the proposition. By (6), BV is mind-independent. But by (1) & (2) & (3), BV is not mind-independent. Contradiction.

Which limb should we reject? We could reject (1). One way would be by maintaining that propositions are abstract (non-spatiotemporal) mind-independent objects (the Frege line). A second way is by maintaining that propositions are concrete (non-abstract) mind-independent objects (the Russell line). Both of these solutions are deeply problematic, however.

Or we could reject (3) and hold that propositions are mental constructions out of mind-independent elements. Not promising!

Or we could reject (4) and hold that reference is always sense-mediated. Not promising either. What on earth or in heaven is the sense that BV expresses when BV utters 'I'? BV has no idea. He may have an haecceity but he cannot grasp it! So what good is it for purposes of reference? BV does not pick himself out via a sense that his uses of 'I' have, that his uses alone have, and that no other uses could have. His haecceity, if he has one, is ineffable.

So pick your poison.

By the way, I have just illustrated the utility of the aporetic style. Whereas what Ed says above is somewhat mushy, what I have said is razor-sharp. All of the cards are on the table and you can see what they are. We seem to agree that there is a genuine problem here.

- There is spoken and written language, and language has composition with varying degrees of granularity. Written language has books, chapters, paragraphs, sentences and words. The sentence is an important unit, which is used to express true and false statements. [The declarative sentence, leastways.]

- Spoken and written language has meaning. Meaning is also compositional, and mirrors the composition of the language at least at the level of the sentence and above. There is no complete agreement about compositionality below the level of the sentence. E.g. Aristotelian logic analyses 'every man is mortal' differently from modern predicate logic. [Well, there is agreement that there is compositionality of meaning; but not what the parsing ought to be.]

- The meaning of a sentence is sometimes called a 'proposition' or a 'statement'. [Yes, except that 'statement' picks out either a speech act or the product of a speech act, not the meaning (Fregean Sinn) of a sentence. Frege thought, bizarrely, that sentences have referents in addition to sense, and that these referents are the truth-values.]

- There are also thoughts. It is generally agreed that the structure of the thought mirrors the structure of the proposition. The difference is that the thought is a mental item, and private, whereas the proposition is publicly accessible, and so can be used for communication. [It is true that acts of thinking are private: you have yours and I have mine. But it doesn't follow that the thought is private. We can think the same thought, e.g., that Sharia is incompatible with the values of the English. You are blurring or eliding the distinction between act and accusative.]

- There is also reality. When a sentence expresses a true proposition, we say it corresponds to reality. Otherwise it corresponds to nothing. So there are three things: language, propositions, reality. The problem is to explain the relation between them. [This is basically right. But you shouldnt say that a sentence expresses a proposition; you should say that a person, using a declarative sentence, in a definite context, expresses a proposition. For example, the perfectly grammatical English sentence 'I am here now' expresses no proposition until (i) the contextual features have been fixed, which (ii) is accomplished by some person's producing in speech or writing or whatever a token of the sentence.]

- In particular, what is it that language signifies or means? Is it the proposition? Or the reality? If the latter, we have the problem of explaining propositions that are false. Nothing in reality corresponds to 'the moon is made of green cheese'. So if the meaning of that sentence, i.e. the proposition it expresses, exists at all, then it cannot exist in mind-independent reality. [This is a non sequitur. It can exist in mind-independent reality if it is a Fregean proposition! But you are right that if I say that the Moon is made of green cheese I am talking about the natural satellite of Earth and not about some abstract object.]

- But if a false proposition suddenly becomes true, e.g. "Al is thin" after Al goes on a diet, and if when false it did not correspond to anything in external reality, how can it become identical with the reality? And we say that such a proposition was false, but is now true, i.e. the same thing that was false, is true. But if the reality is identical with the proposition that is now true, and if the same proposition was once false, it follows that the proposition, whether true or false, is not identical with anything in external reality. [One issue here is whether a proposition can change its truth-value. Suppose we say that a sentence like 'Al is fat' is elliptical for 'Al is fat on Jan 1, 2015.' The latter sentence expresses a Fregean proposition whose TV does not change. Fregean propositions are context-free: free of indexical elements including tenses of verbs. And who ever said that correspondence is identity?]

- It follows that the relation between language and reality is indirect, i.e. always mediated by a proposition. A sentence, to be meaningful at all, signifies or expresses a proposition, and a relation between the proposition and reality exists if the proposition is true, but not when the proposition is false. [I'll buy that.]

- But what sort of thing is a proposition? It is a publicly available object, i.e. available to the common mind, not a single mind only, but not part of external mind-independent reality either. [You are asking a key question: What is a proposition? It is a bitch for sure. But look: both Fregean and Russellian propositions are parts of external mind-independent reality. Do you think those gentlemen were completely out to lunch? Can you refute them? Will you maintain that propositions are intentional objects?]

- We also have the problem of singular propositions, i.e. propositions expressed by sentences with an unquantified subject, e.g. a proper name. It is generally agreed that the composition of singular sentences mirrors the structure of the corresponding proposition. In particular the singular subject in language has a corresponding item in the proposition. Thus the proposition expressed by 'Socrates is bald' contains an item exactly corresponding to the word 'Socrates'.

- But if propositions are always separate from external reality, i.e. if the propositional item corresponding to 'Socrates' is not identical with Socrates himself, what is it? [You could say that it is a Fregean sense. But this is problematic indeed for reasons I already alluded to anent haecceity.]

- Russell's answer was that singular sentences, where the subject is apparently unquantified, really express quantified propositions. If so, this easily explains how the proposition contains no components identical with some component of reality. [Right.]

- But it is now generally agreed that Russell was wrong about proper name sentences. Proper names are not descriptions in disguise, and so proper name propositions are not quantified. So there is some propositional item corresponding to the linguistic item 'Socrates'. [And that item is Socrates himself! And that is very hard to swallow.]

- But if the proper name is not descriptive, it seems to follow that the singular proposition cannot correspond to anything mental, either to a single mind or the group mind. Therefore it must be something non-mental, perhaps Socrates himself. [Or rather, as some maintain, the ordered pair consisting of Socrates and the property of being bald. You see the problem but you are not formulating it precisely enough. When I think the thought: Socrates is bald, I cannot possibly have S. himself before my mind. My mind is finite whereas he is infintely propertied.]

- This means that sentences containing empty names cannot be meaningful, i.e. cannot express propositions capable of truth or falsity. [I think so.]

- This is counter-intuitive. It is intuitively true that the sentence "Frodo is a hobbit" expresses or means something, and that the meaning is composed of parts corresponding to 'Frodo' and 'is a hobbit'. But the part corresponding to 'Frodo' cannot correspond to or signify anything in external reality, i.e. mind-independent reality. [Yes]

- So what does 'Frodo' mean? [You could try an 'asymmetrical' theory: in the case of true singular sentences, the proposition expressed is Russellian, while in the case of false singular sentences the proposition expressed is Fregean. Of course that is hopeless.]

Appeasement of Muslim Fanatics Did Not Begin with Barack Obama

It only got worse under his 'leadership.' David Harsanyi:

. . . the gratuitous groveling we do to allay the sensitivities of violence-prone Muslims (because who else are we attempting to placate?) has become a cringe-worthy aspect of American policy long before Barack Obama ever showed up. When the Bush administration, in the middle of the Danish carton controversy, claimed that “Anti-Muslim images are as unacceptable as anti-Semitic images, as anti-Christian images or any other religious belief,” it was equally wrong. As far as the state goes, they’re all “acceptable.”

But only one of those can put you on kill lists.

After the deadly terrorist attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris, France, it’s worth remembering that there is no amount of conciliating rhetoric that will stop attacks on our liberal values – even undermining them. Which is something we’ve done.

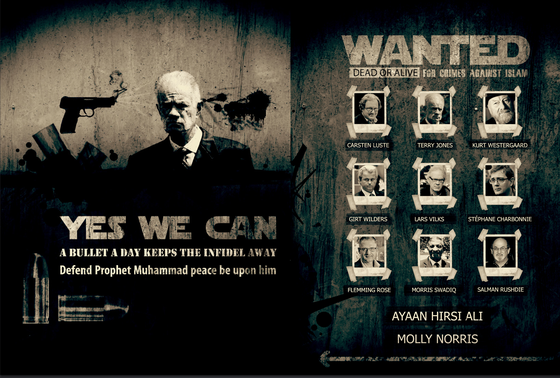

Remember Molly Norris whose name appears on the above poster? I wrote about her on 16 September 2010:

Cartoonist Molly Norris Driven into Hiding by Muslim Extremism

Story here.

Among the great religions of the world, where 'great' is to be taken descriptively not normatively, Islam appears uniquely intolerant and violent. Or are there contemporary examples of Confucians, Taoists, Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, or Christians who, basing themselves on their doctrines, publically issue and carry out credible death threats against those who mock the exemplars of their faiths? For example, has any Christian, speaking as a Christian, publically put out a credible murder contract on Andres Serrano for his despicable "Piss-Christ"? By 'credible,' I mean one that would force its target, if he were rational, to go into hiding and erase his identity?

UPDATE 9/19/2010. Commentary by James Taranto here.

Levels of Reality and the Essence of Religion

Reading John Anderson has enhanced my sense of the centrality of the question of levels of reality for those of us who view philosophy as a quest for the Absolute and a project of self-transformation. Of course it was more or less obvious to me all along, Plato's Allegory of the Cave being the richest depiction we have of the two-world theme.

Essential to religion is the belief that there is what William James calls an "unseen order" (Varieties of Religious Experience, 53), a higher order, above or behind the phenomenal order of time and change, doubt and confusion, mendacity and evil.

The unseen order is to be affirmed without the phenomenal order being denied. So there are two levels of reality. How exactly they are related is the problem, or one problem. We will pursue the problem in due course in connection with John Passmore's discussion of the "Two-Worlds Argument" in his Philosophical Reasoning.

Memory, Matter, Mind

Memory loss points to the materiality of mind while memory's exercise points to its immateriality. Mind is mysterious, but memorial mind is even more so, situated as it is at the crossroads of intentionality and time.

Harvard Faculty Crimson Over ObamaCare

A entirely typical example of liberals who want to do good, so long as it is with other people's money. And that reminds me of a cartoon that should resonate at this time of year.

God as an Ontological Category Mistake

John Anderson's rejection of God is radical indeed. A. J. Baker writes:

Anderson, of course, upholds atheism, though that is a rather narrow and negative way of describing his position given its sweep in rejecting all rationalist conceptions of essences and ontological contrasts in favour of the view that whatever exists is a natural occurrence on the same level of existence as anything else that exists. From that position it follows, not merely that the traditional 'proofs' of the existence of God can be criticised, but that the very conception of a God or a supernatural way of being is an illogical conception — God is an ontological category mistake as we may say. (Australian Realism: The Systematic Philosophy of John Anderson, Cambridge UP, 1986, 118-119)

If someone said that the average thought has such-and-such a volume, you would not say that he was factually incorrect; you would say that he had committed a category mistake inasmuch as a thought is not the sort of item that could have a volume: it is categorially disbarred from having a volume. Someone who says that God exists is saying that there exists something whose mode of being is unique to it and that everything other than God has a different mode of being. But the idea that there are two or more modes of being or two or more levels of reality, according to Anderson, is 'illogical" and ruled out by the exigencies of rational discourse itself. To posit God, then, is to involve oneself in a sort of ontological category mistake, in the words of A. J. Baker.

Let's see if we can understand this. (This series of entries is booked under Anderson, John.)

The Andersonian thesis is an exceedingly strong one: the very concept of God is said to be illogical. It is illogical because it presupposes the notion, itself illogical, that there are levels of reality or modes of existence or ways of being. What makes the argument so interesting is the implied claim that the very nature of being rules out the existence of God. So if we just understand what being is we will see that God cannot exist! This is in total opposition to the tack I take in A Paradigm Theory of Existence (Kluwer 2002) wherein I argued from the nature of existence to (something like) God, and to the tack taken by those who argue from truth to God.

The Andersonian argument seems to be as follows:

1. There is a single way of being.

2. The single way of being is spatiotemporal or natural being.

3. If God exists, then his way of being is not spatiotemporal or natural.

Therefore

4. God does not exist.

Note that the argument extends to any absolute such as the One of Plotinus or the Absolute of F. H. Bradley or the Paradigm Existent of your humble correspondent. Indeed, it extends to any non-spatiotemporal entity.

The crucial premise is (1). For if 'way of being' so much as makes sense, then surely (3) is true. And anyone who accepts (1) ought also to accept (2) given that it is evident to the senses that there are spatiotemporal items. So the soundness of the argument pivots on (1). But what is the argument for (1)?

Note that (1) presupposes that 'way of being' makes sense. This is not obvious. To explain this I first disambiguate 'There are no ways of being.' Someone who claims that there are no ways of being could mean either

A. There are no ways of being because there is a single way of being.

or

B. There are no ways of being because the very idea of a way of being, whether one or many, either makes no sense or rests on some fallacious reasoning: either a thing exists or it does not. There is no way it exists. We can distinguish between nature (essence) and existence but not among nature, existence and way of existence. What is said to belong to the way a thing exists really belongs on the side of its nature. A drastic difference such as that between a rock and a number does not justify talk of spatiotemporal and non-spatiotemporal ways of being: the drastic difference is just a difference in their respective natures.

Many philosophers have championed something like (B). (See Reinhard Grossmann Against Modes of Being. Van Inwagen, too, takes something like the (B)-line.) If (B) is true, then Anderson's argument collapses before it begins. But I reject (B). So I can't dismiss the argument in this way.

Anderson's view is (A). The problem is not with the concept of a way of being; the problem is with the idea that there is more than one way of being. This is clear from his 1929 "The Non-Existence of Consciousness," reprinted in Studies in Empirical Philosophy, wherein we read, "If theory is to be possible, then, we must be realists; and that involves us in . . . the assertion of a single way of being (as contrasted with 'being ultimately' and 'being relatively') [a way of being] which the many things that we thus recognise have." (SEP 76) Thus what Anderson opposes is a duality, and indeed every plurality, of ways of being, and not the very notion of a way of being. One could say that Anderson is a monist when it comes to ways of being, not a pluralist. To invoke a distinction made by John Passmore, one to be discussed in a later entry, Anderson is an existence-monist but not an entity-monist.

Now what's the argument for (1)? As far as I can tell the argument is something like this:

5. Truth is what is conveyed by the copula 'is' in a (true) proposition.

6. There is no alternative to 'being' or 'not being': a proposition can only be true or false.

Therefore

7. There are are no degrees or kinds of truth: no proposition is truer than any other, and there are no different ways of being true. (5, 6)

8. (True) propositions are concrete facts or spatiotemporal situations: propositions are not intermediary entities between the mental and the extramental. They are not merely intentional items, nor are they Fregean senses. The proposition that the cat is on the mat just is the concrete fact of the cat's being on the mat. And the same goes for the cat: the cat is identical to a proposition. Anderson's student, Armstrong, holds that a thick particular such as a cat is a proposition-like entity, a state of affairs; but Anderson holds the more radical view that a cat is not merely proposition-like, but is itself a proposition. But if a cat is a proposition, then

9. Being (existence) = truth.

Therefore

1. There is a single way of being. (from 7, 9)

Therefore, by the first argument above,

4. God does not exist.

Critique

A full critique is beyond the scope of this entry especially since brevity is the soul of blog, as some wit once said. But what I am about to say is, I think, sufficient to refute the Andersonian argument.

If everything exists in the same way, what way is that? Anderson wants to say: the spatiotemporal way. He is committed to the proposition that

A. To be is to be spatiotemporally

where this is to be construed as an identification of being/existence with spatiotemporality. Good classical metaphysician that he is, Anderson is telling us that the very Being of beings, das Sein des Seienden, is their being spatiotemporal.

Now there is a big problem with this. A little thought should convince you that (A) fails as an indentification even if it succeeds as an equivalence: one cannot reduce being/existence to spatiotemporality. For one thing, (A) is circular. It amounts to saying that to exist is to exist in space and time. Now even if everything that exists exists in space and time, the existence of that which exists cannot be identified with being in space and time. So even if (A) is true construed as telling us what exists, it cannot be true construed as telling us what existence is. A second point is that, while it is necessary that a rock be spatiotemporal, there is no necessity that a rock exist, whence it follows that the existence of a rock cannot be identified with its being spatiotemporal.

Now if (A) fails as an identification, it might still be true contingently as an equivalence. It might just happen to be the case that, for all x, x exists iff x is spatiotemporal. But then it cannot be inscribed in the nature of Being (as a Continental philosopher might say) that whatever is is in space and time. Nor can it be dictated by "the nature and possibility of discourse" (SEP 2) or by the possibility of "theory" (SEP 76). Consequently, the Andersonian battle cry "There is only a single way of being!" cannot be used to exclude God.

For any such exclusion of God as an "ontological category mistake" can only proceed from the exigencies of Being itself. What Anderson wants to say is that the very nature of Being logically requires the nonexistence of God. But that idea rests on the confusion exposed above. For his point to go through, he needs (A) to be an identification when at most it is an equivalence.

Gun Control and Liberal-Left Irrationality

The quality of 'elite' publications such as The New Yorker leaves a lot to be desired these days. Adam Gopnik's recent outburst on Newtown is one more example of a downward trend: it is so breathtakingly bad that I am tempted to snark: "I can't breathe!" Could Gopnik really be as willfully stupid as the author of this piece? Or perhaps he was drunk when he posted his screed one minute after midnight on January 1st.

Luckily, I needn't waste any time disembarrassing this leftist goofball of his fallacies and fatuosities since a professional job of it as been done by John Hinderaker and Charles Cooke.

Again I ask myself: why is the quality of conservative commentary so vastly superior to the stuff on the Left?

A tip of the hat and a Happy New Year! to Malcolm Pollack from whom I snagged the above hyperlinks. Malcolm is a very good writer as you can see from this paragraph:

The New Yorker‘s essayist Adam Gopnik — whom I have always considered to be quite lavishly talented, despite his dainty and epicene style — beclowned himself one minute into this New Year with a stupendously mawkish item on gun control. It is so bad, in fact — so completely barren of fact, rational argument, or indeed any serious intellectual effort whatsoever — that I was startled, and frankly saddened, to see it in print. It is the cognitive equivalent, if one can imagine such a thing hoisted into Mr. Gopnik’s rarefied belletrist milieu, of yelling “BOSTON SUCKS” at a Yankees-Red Sox game, at a time when Boston leads the division by eleven games.

A ‘Progressive’ Paradox

Leftists like to call themselves 'progressives.' We can't begrudge them their self-appellation any more than we can begrudge the Randians their calling themselves 'objectivists.' Every person and every movement has the right to portray himself or itself favorably and self-servingly. "We are objective in our approach, unlike you mystics."

But if you are progressive, why are you stuck in the past when it comes to race? Progress has been made in this area; why do you deny the progress that has been made? Why do you hanker after the old days?

It is a bit of a paradox: 'progressives' — to acquiesce for the nonce in the use of this self-serving moniker – routinely accuse conservatives of wanting to 'turn back the clock,' on a number of issues such as abortion. But they do precisely that themselves on the question of race relations. They apparently yearn for the bad old Jim Crow days of the 1950s and '60s when they had truth and right on their side and the conservatives of those days were either wrong or silent or simply uncaring. Those great civil rights battles were fought and they were won, in no small measure due to the help of whites including whites such as Charlton Heston whom the Left later vilified. (In this video clip Heston speaks out for civil rights.) Necessary reforms were made. But then things changed and the civil rights movement became a hustle to be exploited for fame and profit and power by the likes of the race-baiters Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton.

Read almost any race screed at The Nation and similar lefty sites and you wil find endless references to slavery and lynchings and Jim Crow as if these things are still with us. You will read how Trayvon Martin is a latter-day Emmett Till et cetera ad nauseam.

For a race-hustler like Jesse Jackson, It Is Always Selma Again. Brothers Jesse and Al and Co. are stuck inside of Selma with the Oxford blues again.

In case you missed the allusions, it is to Bob Dylan's 1962 Freewheelin' Bob Dylan track, "Oxford Town" and his 1966 Blonde on Blonde track, "Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again."

Wake up you 'progressive' Rip van Winkles! It is not 1965 any more.

I now hand off to Rich Lowry who comments on the movie Selma.

Rethinking and Second Thoughts

To rethink one's position is not necessarily to abandon, question, or revise it. One can rethink without having second thoughts.