Here, at Maverick Philosopher: Strictly Philosophical.

Too Late by Five Months! Remembering Robert C. Coburn

This morning I happened to re-read the chapter "Metaphysical Theology and the Life of Faith" in Robert C. Coburn's, The Strangeness of the Ordinary (Rowman and Littlefield, 1990). I first read it in May of 1997. I was so impressed with it this second time around that I resolved to send Professor Coburn a note of appreciation. But I logged on only to find his obituary. I reproduce it below the fold to save it from the folly and poor judgment of librarians and webmasters. Too late by five months!

Permalinks ought to be permanent, or at least approximate unto the sublunary 'permanence' of that which, under the aspect of eternity, is impermanent.

And it testifies to the poor judgment of librarians that my copy of Coburn's book is a library discard. I was going to tell Coburn that story and praise him for his flawless prose that displays the erudition of a technical philosopher wedded to the deep humanity of a serious truth seeker. As academic philosophy succumbs to leftist infestation, and the humanities dissolve into politically correct nonsense, people of Coburn's depth and breadth of learning are unlikely to be replaced.

Note to Vito C.: you will profit from reading the chapter in question. See if you can find the book in a library. You can access a copy of the chapter's article precursor online, but the fee is ridiculous. If you want, I will send you a photocopy, gratis, if you send me by e-mail your preferred mailing address.

Continue reading “Too Late by Five Months! Remembering Robert C. Coburn”

Should Libertarians Support Open Borders?

Maybe not. It might not be in their best, long-term self-interest, assuming that they are more than a discussion society and want to see their values implemented politically. Libertarians stand for limited government, individual liberty, private property, and free markets. On these points I basically agree with them, although I am not a libertarian. But they don't seem adept at thinking in cultural as opposed to economic terms.

They need to ask themselves whether the culture of libertarianism, its ensemble of values and attitudes, is likely to flourish north of the Rio Grande if an endless stream of mainly Hispanic immigrants is allowed into the country. I suspect that these newcomers will swell the ranks of the Democrats and insure the triumph of socialism when that is presumably what libertarians oppose.

Libertarians may be in a bind similar to the bind Sierra Club types are in. The latter, being 'liberals,' must oppose Trump's Wall of Hate which is of course immoral and divisive and racist. But the porosity of the southern border leads to very serious environmental degradation — which is presumably what Sierra Club types oppose.

Libertarians are like Marxists in their overemphasis on the economic. And like Marxists, their understanding of human nature is deeply flawed. They think of human being as rational actors — which is obviously not the case. The vaunted rationality of the human animal is only in rare cases consistently actual; in most it remains mainly potential, and in some not even that. There can be no sound politics without a sound philosophical anthropology, i.e., a correct understanding human nature.

Sensory Metaphors of Vanity

The empty aspect of the world. Or, exchanging an aural metaphor for the visual: this world rings hollow. In tactile terms: it's slippery, flimsy. And it stinks because it's rotten. The food that supplies us has a limited shelf life and so do we. And it leaves a bad taste in our mouths. We speak of bitter experiences and of people who are embittered. But life can be sweet as well. You call your lady love 'sweetie.'

Related:

To Write Well, Read Well

To write well, read well. Read good books, which are often, but not always, old books. If you carefully read, say, William James' Varieties of Religious Experience, you will learn something of the expository potential of the English language from a master of thought and expression. If time is short, study one of his popular essays such as "The Moral Philosopher and the Moral Life." Here is a characteristic paragraph:

But this world of ours is made on an entirely different pattern, and the casuistic question here is most tragically practical. The actually possible in this world is vastly narrower than all that is demanded; and there is always a pinch between the ideal and the actual which can only be got through by leaving part of the ideal behind. There is hardly a good which we can imagine except as competing for the possession of the same bit of space and time with some other imagined good. Every end of desire that presents itself appears exclusive of some other end of desire. Shall a man drink and smoke, or keep his nerves in condition? — he cannot do both. Shall he follow his fancy for Amelia, or for Henrietta? — both cannot be the choice of his heart. Shall he have the dear old Republican party, or a spirit of unsophistication in public affairs? — he cannot have both, etc. So that the ethical philosopher's demand for the right scale of subordination in ideals is the fruit of an altogether practical need. Some part of the ideal must be butchered, and he needs to know which part. It is a tragic situation, and no mere speculative conundrum, with which he has to deal. (The Will to Believe, Dover 1956, pp. 202-203, emphases in original)

One who can appreciate that this is good writing is well on the way to becoming a good writer. The idea is not so much to imitate as to absorb and store away large swaths of such excellent writing. It is bound to have its effect. Immersion in specimens of good writing is perhaps the only way to learn what good style is. It cannot be reduced to rules and maxims. And even if it could, there would remain the problem of the application of the rules. The application of rules requires good judgment, and one can easily appreciate that there cannot be rules of good judgment. This for the reason that the application of said rules would presuppose the very thing — good judgment — that cannot be reduced to rules. Requiring as it does good judgment, good writing cannot be taught, which is why teaching composition is even worse in point of frustration than teaching philosophy. Trying to get a student to appreciate why a certain formulation is awkward is like trying to get a nerd to understand why pocket-protectors are sartorially substandard.

But what makes James' writing good? It has a property I call muscular elegance. The elegance has to do in good measure with the cadence, which rests in part on punctuation and sentence structure. Note the use of the semi-colon and the dash. These punctuation marks are falling into disuse, but I say we should dig in our heels and resist this decadence especially since it is perpetrated by many of the very same politically correct ignoramuses who are mangling the language in other ways I won't bother to list. There is no necessity that linguistic degeneration continue. We make the culture what it is, and we get the culture or unculture we deserve.

As for the muscularity of James' muscular elegance, it comes though in his vivid examples and his use of words like 'pinch' and 'butchered.' His is a magisterial weaving of the abstract and the concrete, the universal and the particular. Bare of flab, this is writing with pith and punch. And James is no slouch on content, either.

C. S. Lewis somewhere says something to the effect that reading one's prose out loud is a way to improve it. I would add to this Nietzsche's observation that

Good prose is written only face to face with poetry. For it is an uninterrupted, well-mannered war with poetry . . . (Gay Science, Book II, Section 92, tr. Kaufmann)

A well-mannered war, a loving polemic. There is a poetic quality to the James passage quoted above, but the lovely goddess of poetry is given to understand that truth trumps beauty and that she is but a handmaiden to the ultimate dominatrix, Philosophia. Or to coin a Latin phrase, ars ancilla philosophiae.

Finally, a corollary to the point that one must read good books to become a good writer: watch your consumption of media dreck. Avoid bad writing, and when you cannot, imbibe it critically.

Hemingway on Wolfe

Is Line Editing a Lost Art? Excerpt:

Manuscripts, and spirits, are often saved by line editors. Ernest Hemingway began an October 1949 letter to Charles Scribner already in a mood: “The hell with writing today.” Then he opines about editor Maxwell Perkins and the novelist Thomas Wolfe: “If Max hadn’t cut ten tons of shit out of Wolfe everybody would have known how bad it is after the first book. Instead only pros like me or people who drink wine, not labels, know.” Years earlier, Hemingway had warned Perkins about his personality: “please remember that when I am loud mouthed, bitter, rude, son of a bitching and mistrustful I am really very reasonable and have great confidence and absolute trust in you.”

MavPhil suggestion: delete the commas in the initial sentence. Read the sentence out loud both ways and you will see that I am right.

Hyphens are a source of writerly vexation. I would have written 'loud-mouthed.' Papa was probably into his cups.

The Harder I Work . . .

. . . the more 'privileged' I become.

Conflict Resolution, Troubling Trends, and ‘Liberal’ Bias

This from a New York Times article:

“People are making up stories about ‘the other’ — Muslims, Trump voters, whoever ‘the other’ is,” she said. “‘They don’t have the values that we have. They don’t behave like we do. They are not nice. They are evil.’”

She added: “That’s dehumanization. And when it spreads, it can be very hard to correct.”

Dr. Green is now among a growing group of conflict resolution experts who are turning their focus on the United States, a country that some have never worked on. They are gathering groups in schools and community centers to apply their skills to help a country — this time their own — where they see troubling trends.

They point to dehumanizing political rhetoric — for example President Trump referring to the media as “enemies of the people,” or to a caravan of migrants in Mexico as riddled with criminals and “unknown Middle Easterners.”

I beg to differ. When we conservatives point out that Muslims do not share our values, we are not making up stories about them. We are telling the truth. Our classically liberal, American, Enlightenment values are incompatible with Sharia. That is a fact. It is not an expression of racism, xenophobia, or any sort of bigotry. It is not even a judgment as to the quality of their values.

And because Muslims have different values, they behave differently. This is perfectly obvious, and to point it out should offend no one.

Does every Muslim uphold Sharia? No. The great American Zuhdi Jasser does not. But he is an outlier.

To describe Muslims and their values and patterns of behavior is not to 'dehumanize' them. They are human all right; it is just that their values and views make living with them them difficult if not impossible. There can be no comity without commonality.

'Liberals' make the mistake of thinking that 'deep down' we are really all the same and want the same things. That is plainly false.

Trump exaggerates and is careless in his use of language. He is a builder and a promoter, not a wordsmith. He speaks with the vulgar, but the learned who are not hopelessly biased against him know how to 'read' and 'translate' him. I will give one example, and you can work out the others for yourself if you have the intelligence and moral decency to do so.

"The media are enemies of the people." Translation: the mainstream media outlets with the exception of Fox News are dominated by 'progressives' and coastal elitists whose attitudes and values are at odds with the "deplorable" (Hillary's term of abuse) denizens of fly-over country who "cling to their guns and religion" (Obama's abusive phrase).

The values that patriotic Americans cherish are routinely ridiculed and rejected by left-wing media poo-bahs. In this sense, they are enemies of the people.

Contrary to what 'liberals' maintain, Trump is not launching an attack on the Fourth Estate as such. He is attacking the blatant and pervasive left-wing bias of most of their members, bias which is evident to everyone except those members and the consumers of what cannot be called reportage but must be called leftist propaganda.

Article here.

The Self-Reliant Don’t Snivel

Louis L’Amour, Education of a Wandering Man, Bantam, 1989, p. 180:

Times were often very rough for me but I can honestly say that I never felt abused or put-upon. I never felt, as some have, that I deserved special treatment from life, and I do not recall ever complaining that things were not better. Often I wished they were, and often found myself wishing for some sudden windfall that would enable me to stop wandering and working and settle down to simply writing. Yet it was necessary to be realistic. Nothing of the kind was likely to happen, and of course, nothing did.

I never found any money; I never won any prizes; I was never helped by anyone, aside from an occasional encouraging word – and those I valued. No fellowships or grants came my way, because I was not eligible for any and in no position to get anything of the sort. I never expected it to be easy.

It is very difficult these days to explain the classic American value of self-reliance to 'liberals,' especially that species thereof known as the 'snowflake.' Not understanding it, they mock it, as if one were exhorting people to pull themselves up by their own boot straps.

Van Til on Divine Simplicity and the One and the Many

(Edits added 2/10/19)

Cornelius Van Til rightly distinguishes in God between the unity of singularity and the unity of simplicity. The first refers to God's numerical oneness. "There is and can be only one God." (The Defense of the Faith, 4th ed., p. 31) The second refers to God's absolute simplicity or lack of compositeness: ". . . God is in no sense composed of parts or aspects that existed prior to himself." (ibid.) Van Til apparently thinks that divine simplicity is a Biblical doctrine inasmuch as he refers us to Jer. 10:10 and 1 John 1:5. But I find no support for simplicity in these passages whatsoever. I don't consider that a problem, but I am surprised that anyone would think that a doctrine so Platonic and Plotinian could be found in Scripture. What surprises me more, however, is the following:

The importance of this doctrine [simplicity] for apologetics may be seen from the fact that the whole problem of philosophy may be summed up in the question of the relation of unity to diversity; the so-called problem of the one and the many receives a definite answer from the doctrine of the simplicity of God." (ibid.)

That's an amazing claim! First of all, there is no one problem of the One and the Many: many problems come under this rubric. The problem itself is not one one but many! Here is a partial list of one-many problems:

1) The problem of the thing and it attributes.

A lump of sugar, for example, is one thing with many properties. It is white, sweet, hard, water-soluble, and so on. The thing is not identical to any one of its properties, nor is it identical to each of them, nor to all of them taken together. For example, the lump is not identical to the set of its properties, and this for a number of reasons. Sets are abstract entities; a lump of sugar is concrete. The latter is water-soluble, but no set is water-soluble. In addition, the lump is a unity of its properties and not a mere collection of them. When we try to understand the peculiar unity of a concrete particular, which is not the unity of a set or a mereological sum or any sort of collection, we get into trouble right away. The tendency is to separate the unifying factor from the properties needing unification and to reify this unifying factor. Some feel driven to posit a bare particular or bare substratum that supports and unifies the various properties of the thing. The dialectic that leads to such a posit is compelling for some, but anathema to others. The battle goes on and no theory has won the day.

2) The problem of the set and its members.

In an important article, Max Black writes:

Beginners are taught that a set having three members is a single thing, wholly constituted by its members but distinct from them. After this, the theological doctrine of the Trinity as "three in one" should be child's play. ("The Elusiveness of Sets," Review of Metaphysics, June 1971, p. 615)

A set in the mathematical (as opposed to commonsense) sense is a single item 'over and above' its members. If the six shoes in my closet form a mathematical set, and it is not obvious that they do, then that set is a one-over-many: it is one single item despite its having six distinct members each of which is distinct from the set, and all of which, taken collectively, are distinct from the set. A set with two or more members is not identical to one of its members, or to each of its members, or to its members taken together, and so the set is distinct from its members taken together, though not wholly distinct from them: it is after all composed of them and its very identity and existence depends on them.

In the above quotation, Black is suggesting that mathematical sets are contradictory entities: they are both one and many. A set is one in that it is a single item 'over and above' its members or elements as I have just explained. It is many in that it is "wholly constituted" by its members. (We leave out of consideration the null set and singleton sets which present problems of their own.) The sense in which sets are "wholly constituted" by their members can be explained in terms of the Axiom of Extensionality: two sets are numerically the same iff they have the same members and numerically different otherwise. Obviously, nothing can be both one and many at the same time and in the same respect. So it seems there is a genuine puzzle here. How remove it? See here for more.

3. The problem of the unity of the sentence/proposition.

The problem is to provide a satisfying answer to the following question: In virtue of what do some strings of words attract a truth-value? A truth-valued declarative sentence is more than a list of its constituent words, and (obviously) more than each item on the list. A list of words is neither true nor false. But an assertively uttered declarative sentence is either true or false. For example,

Tom is tired

when assertively uttered or otherwise appropriately tokened is either true or false. But the list

Tom, is, tired

is not either true or false. And yet we have the same words in the sentence and in the list in the same order. There is more to the sentence than its words whether these are taken distributively or collectively. How shall we account for this 'more'?

There is more to the sentence than the three words of which it is composed. The sentence is a truth-bearer, but the words are not whether taken singly or collectively. On the other hand, the sentence is not a fourth thing over and above the three words of which it is composed. A contradiction is nigh: The sentence is and is not the three words.

Some will say that the sentence is true or false in virtue of expressing a proposition that is true or false. On this account, the primary truth-bearer is not the (tokened) sentence, but the proposition it expresses. Accordingly, the sentence is truth-valued because the proposition is truth-valued.

But a similar problem arise with the proposition. It too is a complex, not of words, but of senses (on a roughly Fregean theory of propositions). If there is a problem about the unity of a sentence, then there will also be a problem about the unity of the proposition the sentence expresses on a given occasion of its use. What makes a proposition a truth-valued entity as opposed to a mere collection (set, mereological sum, whatever) of its constituents?

4) The problem of the unity of consciousness.

At Theaetetus 184 c, Socrates puts the following question to Theaetetus: ". . . which is more correct — to say that we see or hear with the eyes and with the ears, or through the eyes and through the ears?" Theatetus obligingly responds with through rather than with. Socrates approves of this response:

Yes, my boy, for no one can suppose that in each of us, as in a sort of Trojan horse, there are perched a number of unconnected senses which do not all meet in some one nature, the mind, or whatever we please to call it, of which they are the instruments, and with which through them we perceive the objects of sense. (Emphasis added, tr. Benjamin Jowett)

The issue here is the unity of consciousness in the synthesis of a manifold of sensory data. Long before Kant, and long before Leibniz, the great Plato was well aware of the problem of the unity of consciousness. (It is not for nothing that Alfred North Whitehead described Western philosophy as a series of footnotes to Plato.)

Sitting before a fire, I see the flames, feel the heat, smell the smoke, and hear the crackling of the logs. The sensory data are unified in one consciousness of (genitivus objectivus) a self-same object. This unification does not take place in the eyes or in the ears or in the nostrils or in any other sense organ, and to say that it takes place in the brain is not a good answer. For the brain is a partite physical thing extended in space. If the unity of consciousness is identified with a portion of the brain, then the unity is destroyed. For no matter how small the portion of the brain, it has proper parts external to each other. Every portion of the brain, no matter how small, is a complex entity. But consciousness in the synthesis of a manifold is not just any old kind of unity — it is not the unity of a collection, even if the members of the collection are immaterial items — but a simple unity. Hence the unity of consciousness cannot be understood along materialist lines. It is a spiritual unity and therefore an apt model of the divine simplicity.

Back to Van Til

He is wrong to suggest that there is only problem of the One and the Many. The One and the Many is itself both one and many. Whether he is right that it is "the whole problem of philosophy," it is certainly at the center of philosophy. But what could he mean when he claims that the doctrine of divine simplicity solves the problem? It is itself one form of the problem. The problem is one that arises for the discursive intellect, and is perhaps rendered insoluble by the same intellect, namely, the problem of rendering intelligible the unities lately surveyed.

God is the Absolute and as such must be simple. But divine simplicity is incomprehensible to the creaturely intellect which is discursive and can only think in opposites. What is actual is possible, however, and what is possible might be such whether or not we can understand how it is possible. So the best I can do in trying to understand what Van Til is saying is as follows. He 'simply' assumes that the God of the Bible is simple and does not trouble himself with the question of how it is possible that he be simple. Given this assumption, there is no problem in reality of as to how God can be both one and many. And if there is no problem in the supreme case of the One and the Many, then there are no problems in any of the lesser cases.

Truth and Falsity from a Deflationary Point of View

The following equivalence is taken by many to support the deflationary thesis that truth has no substantive nature, a nature that could justify a substantive theory along correspondentist, or coherentist, or pragmatic, or other lines. For example, someone who maintains that truth is rational acceptability at the ideal (Peircean) limit of inquiry is advancing a substantive theory of truth that purports to nail down the nature of truth. Here is the equivalence:

1) <p> is true iff p.

The angle brackets surrounding a declarative sentence make of it a name of the proposition the sentence expresses. For example, <snow is white> – the proposition that snow is white — is true iff snow is white. (1) suggests that the predicate ' ___ is true' does not express a substantive property. We can dispense with the predicate and say what we want without it. It suggests that there is no such legitimate metaphysical question as: What is the nature of truth? Having gotten rid of truth, can we get rid of falsity as well?

A false proposition is one that is not true. This suggests that 'false,' as a predicate applicable to propositions and truth-bearers generally, is definable in terms of 'true' and 'not.' Perhaps as follows:

2) <p> is false iff <p> is not true.

From (2) we may infer

2*) <p> is false iff ~(<p> is true)

and then, given (1),

2**) <p> is false iff ~p.

This suggests that if we are given the notions of 'proposition' and 'negation,' we can dispense with the supposed properties of truth and falsity. (1) shows us how to dispense with 'true' and (2**) show us how to dispense with 'false.'

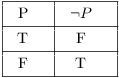

But we hit a snag when we ask what 'not' means. Now the standard way to explain the logical constants employs truth tables. Here is the truth table for the logician's 'not' which is symbolized by the tilde, '~'.

But now we see that our explanation is circular. We set out to explain the meaning of 'false' in terms of 'not' only to find that 'not' cannot be explained except in terms of 'false.' We have moved in a circle.

The Ostrich has a response to this:

. . . we can define negation without reaching for the notions of truth and falsity. Assume that the notion of ‘all possible situations’ is coherent, and suppose it is coherent for any proposition ‘p’ to map onto a subset of that set. Then ‘not p’ maps onto the complement. The question is whether the very idea of a complement of a subset covertly appeals to the concept of negation. But then that suggests that negation is a primitive indefinable concept, rather than what you are claiming (namely that it is truth and falsity which are primitive).

So let's assume that there is a set S of possible worlds,and that every proposition (except impossible propositions) maps onto to an improper or a proper subset of S. The necessary propositions map onto the improper subset of S, namely S itself. Each contingent proposition p maps onto a proper subset of S, but a different proper subset for different propositions. If so, ~p maps onto the complement of the proper subset that p maps onto. And let's assume that negation can be understood in terms of complementation.

The most obvious problem with the Ostrich response is that it relies on the notion of a proposition. But this notion cannot be understood apart from the notions of truth and falsity. Propositions are standardly introduced as the primary vehicles of the truth-values. They alone are the items appropriately characterizable as either true or false. Therefore, to understand what a proposition is one must have an antecedent grasp of the difference between truth and falsity.

To understand the operation of negation we have to understand that upon which negation operates, namely, propositions, and to understand propositions, we need to understand truth and falsity.

A second problem is this. Suppose contingent p maps onto proper subset T of S. Why that mapping rather than some other? Because T is the set of situations or worlds in which p is true . . . . The circularity again rears its ugly head.

The Ostrich, being a nominalist, might try to dispense with propositions in favor of declarative sentences. But when we learned our grammar back in grammar school we learned that a declarative sentence is one that expresses a complete thought, and a complete thought is — wait for it — a proposition or what Frege calls ein Gedanke: not a thinking, but the accusative of a thinking.

Truth and falsity resist elimination.

Language Rant: Verbal Inflation and Deflation

The visage of Jeff Dunham's 'Walter' signals the onset of a language rant should you loathe this sort of thing.

Why use ‘reference’ as a verb when ‘refer’ is available? Why not save bytes? Why say that Poindexter referenced Wittgenstein when you can say that he referred to the philosopher? After all, we do not say that X citationed Y, but that X cited Y. (And please don’t confuse ‘site,’ ‘sight,’ and ‘cite.’)

You will not appear learned to the truly learned if you use ‘reference’ as a verb; you will appear pseudo-learned or pretentious. Of course, if enough people do it, it will become accepted. But what is accepted ought not be confused with the acceptable in the normative sense of the latter term. Admittedly, using ‘reference’ as a verb is no big deal. But it is uneconomical, and linguistic bloat, like other forms, is best avoided. This rule, like all my rules and recommendations, is to be understood ceteris paribus. Thus there may be an occasion on which a bit of bloat is what is needed for some rhetorical purpose. Good writing cannot be reduced to the mechanical application of a set of rules. You won’t find an algorithm for it. Language Nazis like me need to remind ourselves not to become too pedantic and persnickety.

Curiously enough, the same people who are likely to engage in verbal inflation will also fall for the opposite mistake. They will speak of Nietzsche quotes when they mean Nietzsche quotations. ‘Quote’ is a verb; ‘quotation’ a noun. ‘Nietzsche quotes’ is a sentence; ‘Nietzsche quotations’ is not. Perhaps I should be grateful that no one, so far, has used ‘quotation’ as a verb: Poindexter referenced Nietszche in his footnotes, and quotationed him in his text.

Now consider ‘criticize,’ ‘criticism,’ and ‘critique.’ One verb and two nouns. Don’t say: She critiqued my paper; say she criticized it. And don’t confuse a criticism with a critique. A correspondent once made a pusillanimous criticism of an article of mine, but referred to it as a critique. That’s a case of objectionable verbal inflation.

On a more substantive note, realize that to criticize is not to oppose or contradict, but to sift, to assay, to separate the good from the bad, the beautiful from the ugly, the true from the false, the demonstrated from the undemonstrated and the indemonstrable.

Note also that the Left does not own critique. There is critique from the Right, from the Left, and from the Middle. Resist the hijacking of semantic vehicles. We need them to get to the truth, which is not owned by anyone.

Excluded Middle, Presentism, Truth-Maker: An Aporetic Triad

Suppose we acquiesce in the conflation of Excluded Middle and Bivalence. The conflation is not unreasonable. Now try this trio on for size:

Excluded Middle: Every proposition is either true, or if not true, then false.

Presentism: Only what exists at present, exists.

Truth-Maker: Every contingent truth has a truth-maker.

The limbs of the triad are individually plausible but collectively inconsistent. Why inconsistent?

I will die. This future-tensed sentence is true now. It is true that I will die. Is there something existing at present that could serve as truth-maker? Arguably yes, my being mortal. I am now mortal, and my present mortality suffices for the truth of 'I will die.' Something similar holds for my coat. It is true now that it will cease to exist. While it is inevitable that I will die and that my coat will cease to exist, it is not inevitable that my coat will be burnt up (wholly consumed by fire). For there are other ways for it to cease to exist, by being cut to pieces, for example, or by just wearing out.

By 'future contingent,' I mean a presently true future-tensed contingent proposition. The following seems to be a clear example: BV's coat will sometime in the future cease to exist by being wholly consumed in a fire. To save keystrokes: My coat will be burnt up.

By Excluded Middle, either my coat will be burnt up or my coat will not be burnt up. One of these propositions must be true, and whichever one it is, it is true now. Suppose it is true now that my coat will be burnt up. There is nothing existing at present that could serve as truth-maker for this contingent truth. And given Presentism, there is nothing existing at all that could serve as truth-maker. For on Presentism, only what exists now, exists full stop. The first two limbs, taken in conjunction, entail the negation of the third, Truth-Maker. The triad is therefore inconsistent.

So one of the limbs must be rejected. Which one?

An Objection

You say that nothing that now exists could serve as the truth-maker of the presently true future-tensed contingent proposition BV's coat will be burnt up. I disagree. If determinism is true, then the present state of the world together with the laws of nature necessitates every later state. Assuming the truth of the proposition in question, there is a later state of the world in which your shabby coat is burnt up. The truth-maker of the future contingent proposition would then be the present state of the world plus the laws of nature. So if determinism is true, your triad is consistent, contrary to what you maintain, and we will not be forced to give up one of the very plausible constituent propositions.

Question: Is there a plausible reply to this objection? No. I'll explain why later.

The State of the Union

President Trump gave a great speech last night. I agree with Malcolm Pollack's commentary.

Obviously you can’t please everyone, and there will be many of us who will take issue with some of what Mr. Trump put forward last night. (In particular, I think he is far too enthusiastic about increasing legal immigration, for reasons I won’t go into here.)

That excess of enthusiasm struck me as well, for reasons I too won't go into now. I have plenty to say in my Immigration category.