During his years of unsuccess, when he was actually at his purest and best, an "unpublished freak," as he describes himself in a late summer 1954 letter to Robert Giroux, living for his art alone, Kerouac contemplated entering a monastery: "I've become extremely religious and may go to a monastery before even before you do." [. . .] "I've recently made friends in a way with Bob Lax and I find him sweet — tho I think his metaphysics are pure faith. Okay, that's what it's supposed to be." (Selected Letters 1940-1956, ed. Charters, Penguin 1995, p. 444.)

And then on pp. 446-448 we find an amazing 26 October [sic!] 1954 letter to Robert Lax packed with etymology and scholarly detail which ends:

I'm no saint, I'm sensual, I cant resist wine, am liable to sneers & secret wraths & attachment to imaginary lures before my eyes — but I intend to ascend by stages & self-control to the Vow to help all sentient beings find enlightenment and holy escape from sin and stain of life-body itself [. . .] but thank God I'm a lazy bum because of that repose will come, in repose the secret, and in the secret: Ceaseless Ecstasy.

"Nirvana, as when the rain puts out a little fire."

See you in the world,

Jack K.

For information on the enigmatic hermit Robert Lax (1915-2000) , see here

Robert Lax: A Life Slowly Lived is especially good. Excerpts:

One of the touchstone words in Lax’s spiritual vocabulary was “waiting”. By this he meant being still, standing one’s ground, knowing one’s ground, but never quite knowing the reality of what was awaited, longed for. In his volume 33 Poems, recently reissued by New Directions, he puts it this way:

Wake up & wait. Lie down & wait. Sit up again & wait. All in the dark now. No way of telling day from night. Do I expect to hear a voice? See a light? A dim one? A bright one? See a face? I sit up. I’m alert. Do I know what to expect? [2]

“What you see,” said Paul Spaeth, keeper of the Lax archive at St Bonaventure, “is the opposite of what can be called social action. What you see is a slowing down and waiting on God. Very much in keeping with the monastic tradition. Also very similar to the Buddhist tradition of moment to moment mindfulness.”

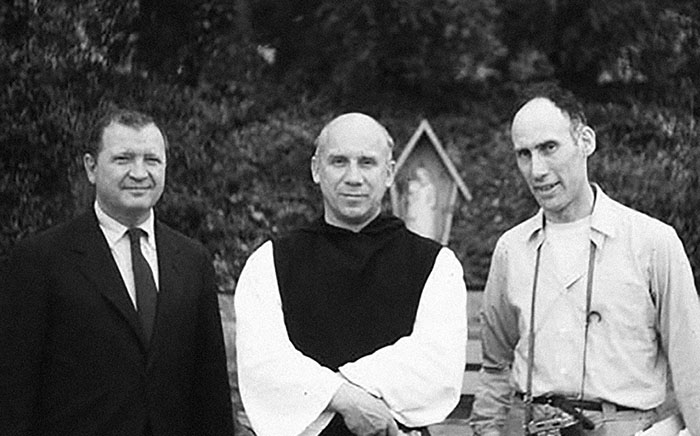

Robert Lax with his two close friends: Thomas Merton (middle) and the abstract painter, Ad Reinhardt (left). Photograph courtesy of the Thomas Merton Center © Bellarmine University

Unlike his friend Thomas Merton, the Trappist poet and author who shared Lax’s interest in Buddhism and brought his name to the world in The Seven Storey Mountain, [3] Lax never lived a life of structured monasticism. A Jewish convert to Catholicism, he built for himself an interior monastery, within which he wrote, prayed, contemplated, and received many visitors: poets, painters, writers (he’d been friends with the legendary abstract artist, Ad Reinhardt, and with Jack Kerouac), and spiritual seekers. “Lax can be thought of as a mystic,” said his biographer Michael N. McGregor, who nevertheless refrained from using that word in his book Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax. [4] He shared his subject’s aversion to the superficiality of labels. He wanted readers to come to their own conclusions about who he was, what he was.

Steve Georgiou, a seeker from California and author of The Way of the Dreamcatcher, a book of dialogues with Lax, remembers their walks down to Skala, the Patmos harbour. “He would walk with a slow roll like the roll of a boat. He would take his meditative steps, encouraging you to slow down yourself and feel the actual experience of walking”. [5]

For Lax, there was no seam between walking, praying, writing. All experiences were to be fully absorbed, integrated into a life fully lived. Once Georgiou saw his friend writing a single word – “river” – over and over. He asked him why. “I want to live with the word for a while,” Lax said.

one word at a time.

I believe

I believe

that all people

should stop their fight;

I believe that one should

blow a whistle or

sing or play

on the

lute [6]

2 responses to “Evil as Privation and the Problem of Pain, Part One (2021 Version)”